Description to the Historical Records Dataset on Human

Activity in the Hexi Corridor of China (from Neolithic to Qing Dynasty)

Gao, M. J.2

Li, Y.1,2*

1 Key

Laboratory of Western China??s Environmental Systems (Ministry of Education),

Lanzhou 730000, China;

2 College

of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China

Abstract: Social responses to

environmental change over human history have generated extensive debate among

researchers. Comprehensive human activity databases are valuable for exploring

the links between human evolution and environmental change. The Hexi Corridor

is a crucial area where eastern and western civilizations met due to its

location in the eastern section of the ancient Silk Road. Here, we present a

comprehensive dataset of the Hexi Corridor, including disasters, population,

wars, famines, and settlements from the Neolithic to the Qing dynasty. These data are mainly from various digitized

historical sources, which have been extracted, digitized, and georeferenced

through a standardized process. The ultimate aim of these data is to provide as

comprehensive a record as possible of human activity in the Hexi Corridor to

support ongoing research on human-environment relations.

Keywords: Hexi Corridor; human activities;

disasters; ancient sites

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2023.02.08

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2023.02.08

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset supporting this paper was published and is accessible through

the Digital Journal of Global Change

Data Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2023.07.09.V1

or https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2023.07.09.V1.

1 Introduction

It

is undoubtedly a serious challenge to modern societies?? political and economic

development rate than ever before[1, 2]. Over the past tens of

thousands of years, human has gone from being dependent on nature to using

nature try to try to develop in harmony with nature, culminating in the present

civilization[3, 4]. Over the past century, research on environmental

change has been mainly concerned with the natural sciences[5, 6]. As

research continues, scientists are finding it increasingly impossible to ignore

the impact of human activity. Using human activity as a thread provides a new

perspective on the relationship between environmental change and human activity

in the research on the relationship between human origins, agricultural

origins, civilizational origins, social development, and climatic and

environmental changes[7?C10]. These research directions have been

implemented and advanced with increasing emphasis on the impact of human

society on global environmental change and the issue of human society??s

response and adaptation to global change. The volume of this work and its

evolving scientific understanding generate organizational challenges associated

with data collection, extraction, validation, and application.

The spatial and

temporal integration of human data involves the spatial differentiation of

complex human activities, and many theoretical and technical problems need to

be overcome, including the spatial distribution of human data, theoretical and

methodological research related to data sampling, and results testing[11].

Compared with natural environmental data, human data are mainly based on human

units rather than natural units in terms of spatial units. This poses problems,

such as difficulty identifying dates, low spatial resolution, differences in

dating methods, and changes in administrative boundaries[12].

The Hexi Corridor

is a typical area of synergistic influence of the mid-latitude westerly

circulation and the Asian monsoon and is a sensitive area for environmental

change[13]. It is located at the throat of the Silk Road. It is an

important route for the spread of prehistoric humanity and cultural exchanges

between East and West, as well as a meeting point for the evolution of

civilizations in Eurasia and a frontier for the clash between Chinese

agricultural and nomadic civilizations[14,15]. Finally, considering

that the Hexi Corridor is the main oasis agricultural and landscape

distribution area in China and worldwide, with significant changes in water

resources and fragile oasis ecosystems, together with the currently hotly

debated warming and humidification of the Northwest and climate hazards, the

region is an area of concern for future climate change[16].

Here, we present a

new database of Holocene paleoclimate human and historical records from the

Hexi Corridor and the adjacent region. This database is composed of records

from individual sample studies and records that are compiled by previous

summaries. This database includes disasters, population, wars, famines, and

settlement records that reflect human activities. All data is published in .xlsx

format. This geographically distributed collection of human activity data

records integrates environmental change as well as human activity

characteristics in the Hexi Corridor region, forming a network from which to

assess the spatial and temporal variability of regional climate change and

human activity.

2 Metadata of

the Dataset

The metadata of the Historical records dataset on

human activity in the Hexi Corridor of China (from Neolithic to Qing dynasty)

is summarized in Table 1[17].

3 Methods

3.1 Data Collection and

Data Extraction

Human activity data are considered for

inclusion in the regional environmental change database. Human history data is

obtained from a wide range of historical sources in China, including various

historical sources such as general histories, ancient maps, annals, and modern

secondary statistics such as government releases, books, modern maps, and some

recent research papers. This dataset is intended to extract data on the

humanities of Gansu province from the Neolithic period to the Qing dynasty, including

ancient sites, ancient cities, disasters, wars, population, and famine. The

processing of the primary data is broken down into the following categories.

(1) War

This

chronology is based on the chronology of the wars that took place in China from

the legendary Shennong era in the 30th century BC to the end of the Qing

dynasty in 1911 and provides a brief account of the causes, course, outcome,

and characteristics of the significant

Table

1 Metadata summary of the digital database of human

activity in the Hexi Corridor[17]

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset full name

|

Historical

records dataset on human activity in the Hexi Corridor of China (from

Neolithic to Qing dynasty)

|

|

Dataset short

name

|

HexiCorridorHumanActivity

|

|

Authors

|

Gao, M. J.

HTR-7743-2023, College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Center for

Hydrologic Cycle and Water Resources in Arid Region, Lanzhou University gaomj21@lzu.edu.cn

Li, Y., Key

Laboratory of Western China??s Environmental Systems (Ministry of Education); College of Earth

and Environmental Sciences, Center for Hydrologic Cycle and Water Resources

in Arid Region, Lanzhou University, liyu@lzu.edu.cn

|

|

Geographical

region

|

the Hexi Corridor

|

|

Year

|

4000 BC?C1900 CE

|

|

Spatial

resolution

|

City and county

|

|

Data format

|

.xlsx, .shp

|

|

|

|

Data size

|

1.78 MB

|

|

|

|

Data files

|

3 datasheets:

ancient city and ancient ruins (including .shp), disaster and famine; wars

|

|

Foundations

|

National Natural

Science Foundation of China (42077415); Ministry of Science and Technology of

P. R. China (2019QZKK0202, BP0618001)

|

|

Data publisher

|

Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository,

http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No. 11A, Datun

Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data sharing

policy

|

Data from the Global Change Research Data

Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets (in the Digital Journal of Global

Change Data Repository), and publications (in the Journal of Global

Change Data & Discovery).

Data sharing

policy includes: (1) Data are openly available and can

be free downloaded via the Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data

subject to citation; (3) Users, who are by definition also value-added

service providers, are welcome to redistribute Data subject to written

permission from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data

redistribution license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new

datasets, the ??ten per cent principal?? should be followed such that Data

records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while

sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[18]

|

|

Communication and

searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR, Crossref, DCI, CSCD, CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

wars[19]. Due to the subjective nature of the records, we have not

compiled statistics on the number of casualties of the wars but merely

extracted the time, place, and type of warfare. For the time of the war, the

imperial chronology was converted into the A.D. chronology by comparing it with

the ancient Chinese chronology. For the location of the war, it has been converted

into a modern location according to Chinese Historical Atlas[20]. We

examined the causes of the wars and divided them into rebellious wars and other

wars[20].

(2) Disaster and famine

The main source of disaster information is the History of Disasters in Northwest China,

a systematic summary of the history of disasters in the Northwest of China

based on hundreds of credible historical documents[21]. and we have

also collected documents published in journals and searched the original

records to check them all and fill in the gaps to reflect the historical

climate more objectively[22?C25]. As historical sources are sometimes

lost after being collated several times, we still consider them reliable but do

not mark them as such.

(3) Population

As in modern societies, population counts are not

conducted annually, and often, feudal rulers would only conduct a census once

during their reign, so the population numbers obtained through historical

sources often vary in time intervals. In order to provide a more comprehensive

picture of the demographic trends in the Hexi Corridor, we have collected the

current continuous demographic studies and, using mathematical methods based on

previous studies, have calculated the population numbers at 50-year intervals[26?C28].

(4) Ancient sites and an cities

The ancient sites and cities??

statistics are based on the Atlas of

Chinese Cultural Relics-Fascicule of Gansu province. The coordinates are

given using the spatial alignment function of ArcGIS to obtain the coordinates

of the spatial location of the protected units and export them to Excel. The

coordinates of the ancient cities are calibrated with the help of Google Maps.

The chronology of the ancient city is calibrated according to the descriptions

in the atlas and combined with archaeological data.

Other human and paleoclimatic records are considered

but ultimately excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria. Most

of the excluded records are either not sufficiently clear in their description

of human activity, e.g., lacking information on elements such as time and place

not credible sources; some wild histories and documents processed several times

lack a clear relationship between proxies and climate, of insufficient duration

or poor regional representation, and not meeting the sampling resolution

criteria.

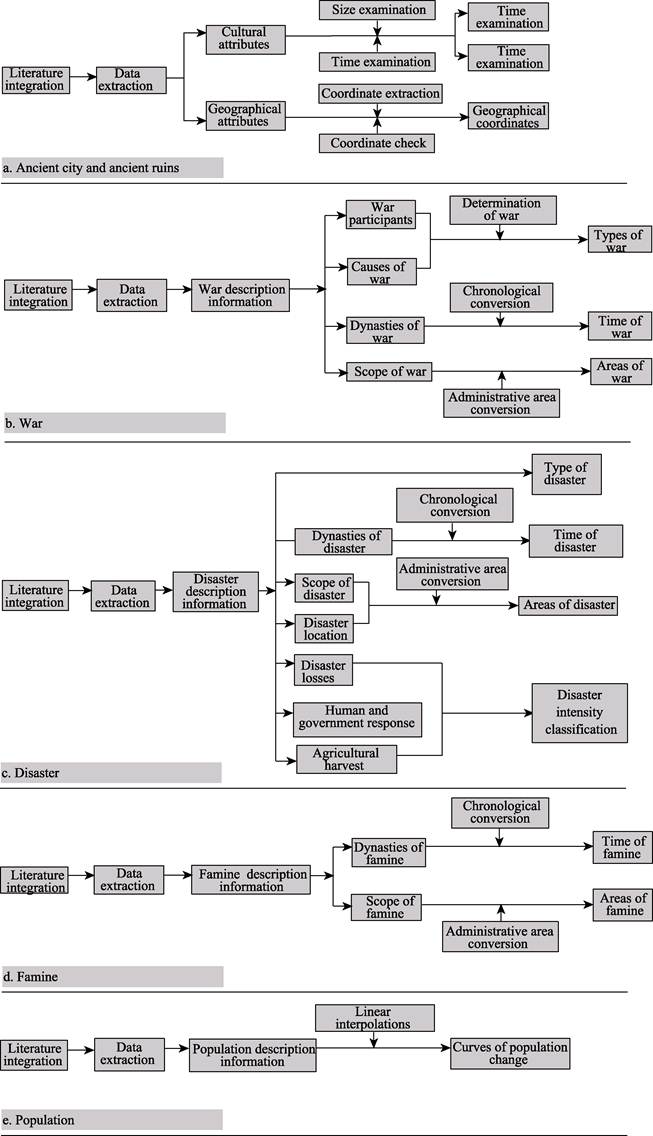

3.2 Technical Workflow

The reconstruction process of

human activity data mainly included (1) Extracting different types of

anthropogenic data from historical sources, and (2) Generating tables and

drawing diagrams of anthropogenic data. Figure 1 shows the workflow for

extracting different types of human activity data.

4 Data Results

and Analysis

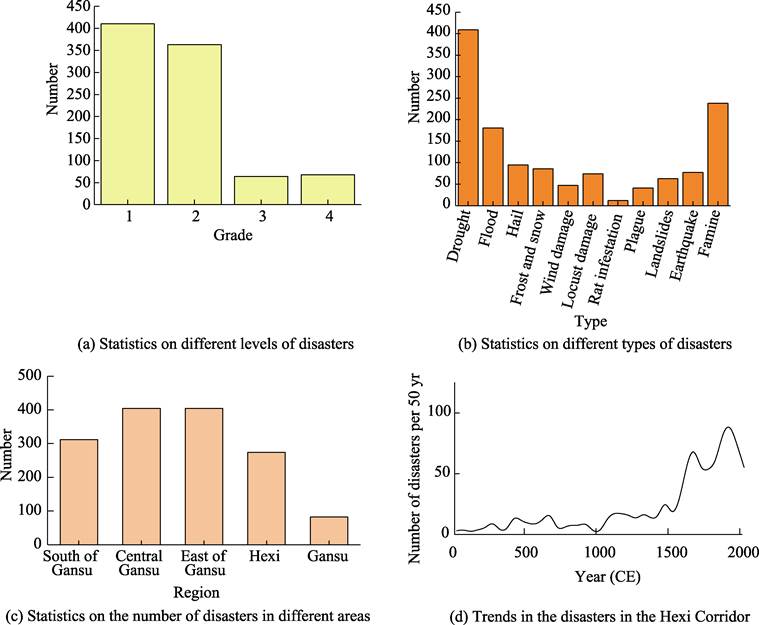

Figure 2 shows the

statistical curves for changes in disasters and famines. We collect and collate

data on 1,085 disasters and information on 238 famines. Droughts and floods are

the main types of disasters in the Hexi Corridor, with the sum of the two

accounting for almost half of the disasters in the Hexi Corridor (Figure 2b). In terms of rank, mild and moderate disasters make up the

majority (Figure 2a). Based on spatial data, the

distribution of disasters in the Hexi Corridor is relatively even, with no

prominent most challenging hit areas (Figure 2c). The Ming and

Qing dynasties (1368 AD-1912 CE) appear to

have been a period of high disaster occurrence, as indicated by the curve of

disasters over time, but this may be because more historical material has

survived from that period (Figure 2d).

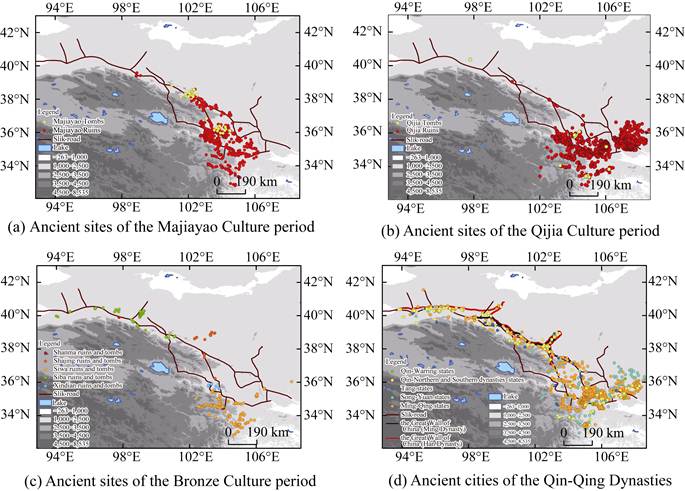

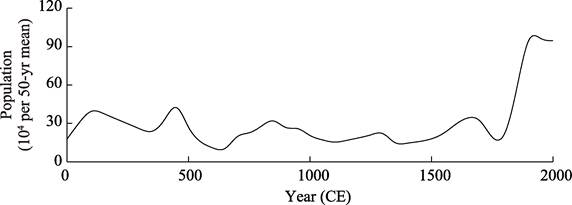

Figure 3 shows the

distribution of ancient sites and cities from the Neolithic period to the Qing

dynasty. Of the 2,077 site points information collected and collated, there are

2005 ancient site points and 72 ancient burial sites. According to the spatial

distribution characteristics, in the early Neolithic period, the site points of

the Majiayao culture were mainly distributed in the eastern part of the

corridor. In contrast, the Qijia culture continued to expand to the east and is

more concentrated (Figure 3ab). The Qijia culture is followed by a period of

richness in ancient cultural types in the Hexi Corridor, and these cultures

begin to migrate to the western part of the corridor. The early sites are

distributed on the highlands according to the DEM features. However, as the

culture developed and the distribution of sites diversified, they also began to

move downstream towards the rivers, seemingly due to increased topographic

adaptation (Figure 3c). The reasons for this phenomenon may be multifaceted and are a matter for further research.

The ancient cities of the Hexi Corridor have been built and abandoned many

times throughout the historical period (Figure 3d). The Silk Road is the

central vein of distribution of the ancient cities, and almost all of them were

built along the Silk Road. During the Qin-North and South dynasties, the

distribution of ancient cities was loose, basically scattered along the

Han Great Wall. From the Song-Yuan period onwards, the focus of the

distribution of ancient cities began to be within the Ming Great Wall, and most

of them fell into disuse. The Ming and Qing dynasties are the period with the

largest number of ancient cities in the Western Corridor, possibly due to the

development of the rulers and the short period that has passed since then,

making them easy to preserve.

Figure 1 Workflow for extracting

different types of human activity data

Figure 2 Statistics of disasters and

famines in the Hexi Corridor.

Figure 3 Maps of data on ancient

sites and ancient cities in the Hexi Corridor

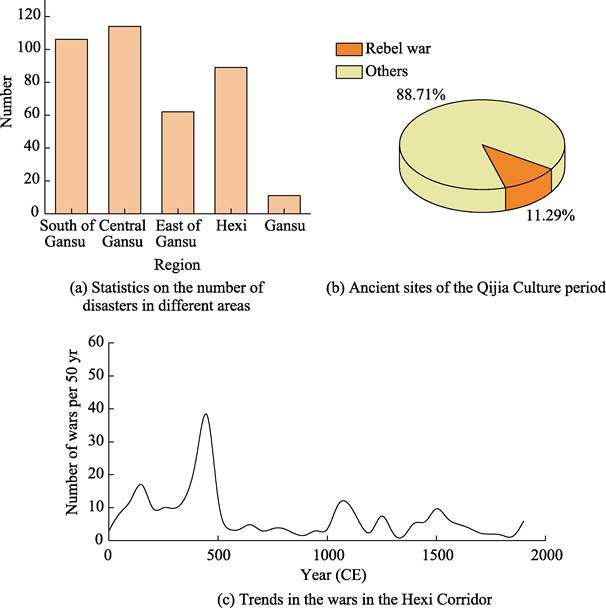

Figure 4 Maps of data on wars in the Hexi Corridor

Central Gansu and South of Gansu are hot

areas of warfare, with few wars spreading throughout Gansu (Figure 4a).

Rebel wars account for only about a tenth of the total number of wars (Figure 4b).

The peak of warfare occurred before 500 CE, after which the population of the

Hexi Corridor reaches its lowest value (Figure 4c,

Figure 5). Many

studies have analyzed the interaction between disaster, famine, war, and

population. Although the curves show consistent or opposite trends, it seems

that this alone is not entirely appropriate. By tracing a specific disaster

event through time and space, we do not find social severe consequences, and

the relationship between extreme events and social unrest remains uncertain.

Figure 5 Trends in the population in the Hexi

Corridor

5 Data Validation

5.1 Quality Control

The collection and extraction

of a digital database of human activity is produced with strict quality control

throughout the procedures. The location of ancient sites and cities is examined

via professional GIS tools (ArcGIS) to ensure the accuracy of their geographic

locations. For wars, disasters, and famines, it is necessary to

match the time and place of occurrence, mainly due to differences in

chronological methods and changes in administrative areas.

5.2 Uncertainties

This study aims to collect

evidence of typical human activities in the Hexi Corridor region. Due to the

complexity of the current sources of human activity data, the following

spatiotemporal mismatches are common, i.e., the periods do not fully coincide,

or the spatial extent does not fully overlap. This is inconvenient for

correcting information from multiple sources and impacts the analysis of

regional patterns. Although we have improved the accuracy of the data through

integration and intercomparison, there is still uncertainty in the description

of regional human activity patterns. For this reason, more efforts are needed

to generate a more accurate database. On the one hand, deeper information

mining on the Hexi Corridor is needed. In the future, we consider collecting

human economic data, such as the extent of arable land and metal production, to

analyze better the relationship between people and the environment in the

region. On the other hand, machine learning will establish a standardized data

extraction process to extract information on human activities in the data more

accurately.

6

Conclusion

Through the collection and

processing of research data related to the historical geography of the Hexi

Corridor (e.g., research papers, books, scientific research reports, etc.), the

database of human activities in the Hexi Corridor was obtained, which is a

secondary development study based on the primary data. In producing the data,

making human judgments on each is necessary, and the production process takes a

long time. The human activity database of the Hexi Corridor obtained by this

method has good accuracy in analyzing the spatial distribution, disaster

evolution, and population change of the whole Hexi site in a long time range.

However, it is less accurate for smaller fields such as counties and townships,

which is mainly limited by the ambiguity of the data source records and the

uncertainty of the administrative range in the historical period. Also, due to

the diversity of data, there are cases of conflict with the original data,

which also results in a decrease of the accuracy of the data.

As an important part of

the Silk Road, the Hexi Corridor has been an essential passage for traders and

the military for nearly a thousand years. Taking the Hexi Corridor as an

example, this database completes a data architecture of human-land relations in

a small region, which can be used to analyze the long-term evolution of human

activities in the context of climate change in a targeted manner and can be

used as a template for other regions seeking to understand their

human-environmental history better.

Author contributions

Li, Y. designed the research; Gao, M.J

implemented the research and analyzed the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors

declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]

Burke,

A., Peros, M. C., Wren, C. D., et al.

The archaeology of climate change: the case for cultural diversity [J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 2021, 118(30): e2108537118.

[2]

Doblas-Reyes,

F. J., Srensson, A. A., Almazroui, M., et

al. IPCC AR6 WGI Chapter 10: Linking Global to Regional Climate Change [M].

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

[3]

Gornitz,

V. Encyclopedia of Paleoclimatology and Ancient Environments: Encyclopedia of

Earth Sciences Series [M], Dordrecht: Springer, 2009.

[4]

Lv,

H. Y. Periodic climate change and human adaptation [J]. Acta Anthropologica Sinica, 2022(4): 41.

[5]

Valero-Garc??s,

B. L., Moreno, A. Iberian lacustrine sediment records: responses to past and

recent global changes in the Mediterranean region [J]. Journal of Paleolimnology, 2011, 46: 319?C325.

[6]

Chen,

F. H., Chen, J. H., Huang, W., et al.

Westerlies Asia and monsoonal Asia: Spatiotemporal differences in climate

change and possible mechanisms on decadal to sub-orbital timescales [J]. Earth-science Reviews, 2019, 192:

337?C354.

[7]

Weiss,

H., Courty, M. A., Wetterstrom, W., et al.

The genesis and collapse of third millennium north Mesopotamian civilization

[J]. Science, 1993, 261(5124):

995?C1004.

[8]

Sarkar,

A., Mukherjee, A. D., Bera, M. K., et al.

Oxygen isotope in archaeological bioapatites from India: Implications to

climate change and decline of Bronze Age Harappan civilization [J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 26555.

[9]

Degroot,

D., Anchukaitis, K., Bauch, M., et al.

Towards a rigorous understanding of societal responses to climate change [J]. Nature, 2021, 591(7851): 539?C550.

[10]

Berrang-Ford,

L., Siders, A. R., Lesnikowski, A., et al.

A systematic global stocktake of evidence on human adaptation to climate change

[J]. Nature Climate Change, 2021,

11(11): 989?C1000.

[11]

Shi,

P., Wang, J., Yang, M., et al.

Understanding of natural disaster database design and compilation of digital

atlas of natural disasters in China [J]. Geographic

Information Sciences, 2000, 6(2): 153?C158.

[12]

Zheng,

J. Y., Hao, Z. X., Di, X. C. A study on the establishment and application of

environmental change database during historical times [J]. Geographical Research, 2002, 21(2): 146?C154.

[13]

Li,

Y., Wang, N. A., Li, Z, L., et al.

Comprehensive analysis of lake sediments in Yanchi Lake of Hexi Corridor since

the late glacial [J]. Acta Geographica

Sinica, 2013, 68(7): 933?C944.

[14]

Barisitz,

S. Central Asia and the Silk Road: Economic Rise and Decline over Several

Millennia [M]. Springer International Publishing, 2017.

[15]

Dong,

G. H., Yang, Y. S., Liu, X. Y., et al.

Prehistoric trans-continental cultural exchange in the Hexi Corridor, northwest

China [J]. The Holocene, 2018, 28(4):

621?C628.

[16]

Li,

X., Gou, X. H., Wang N. L., et al.

Tightening ecological management facilitates green development in the Qilian

Mountains [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin,

2019, 64(27): 2928?C2937.

[17]

Gao,

M. J., Li, Y. Historical records dataset on human activity in the Hexi Corridor

of China (from Neolithic to Qing dynasty) [J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository, 2023.

https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2023.07.09.V1. https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2023.07.09.V1.

[18]

GCdataPR

Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL].

https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated 2017).

[19]

Guo,

R. H. Military history of China [M]. Beijing: PLA Publishing Press, 1986.

[20]

Tan,

Q. X. The historical atlas of China [M]. Beijing: China Cartographic Publishing

House, 1982.

[21]

Yuan,

L. History of disaster and famine in Northwest China [M]. Lanzhou: Gansu

People??s Publishing House, 1994.

[22]

Feng,

S. W. Compilation of historical and climate data on the Qilian Mountain and its

surrounding areas [J]. Northwest

historical geography, 1982(1): 1?C18.

[23]

Li,

B. C. Study on the changes of climate about aridity and humidity in history in

Hexi Corridor [J]. Journal of Northwest

Normal University (Natural Science),

1996, 32(4): 56?C61.

[24]

Yu,

K. K., Zhao, J. B., Luo, D. C. Preliminary study on drought disasters and

drought events in the Hexi Corridor in the Ming and Qing Dynasties [J]. Arid Zone Research, 2011, 28(2):

288?C293.

[25]

Shun,

J. L., He, Y. Q., He, Z., Pang, J. Study on the flood disasters and climate

changes in the Hexi Corridor during Qing dynasty and the Republic of China [J].

Journal of Arid Land Resources and

Environment, 2016, 30(1): 60?C66.

[26]

Zhang,

Y. P., Qi, C. J. Brief description of the population of Hexi past dynasties

[J]. Northwest Population Journal,

1998(2): 6?C12.

[27] Cheng, H. Y.

The desertificcation of the Hexi area in historical time [D]. Lanzhou: Lanzhou

Unversity, 2007.

[28]

Jiang, Q. J. A Study of the Population of Hexi through the Ages [M]. Hohhot:

Inner Mongolia People??s Publishing House, 2008.