Reconstruction Dataset of Cropland Change in Five Central

Asian Countries over the Last

Millennium

Jiang, C. Ye, Y.* Fang, X. Q. Zhang, C. P. Zhang, D. Y.

Faculty of Geographical

Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China

Abstract: Reconstructing land use and

cover change (LUCC) is an important task for global change research. As one of

the important ways to use land, cropland is the focus for the reconstruction of

historical land cover datasets. This study reconstructed the total cropland

area of five Central Asian countries over the last millennium based on

historical documents and used a gridded allocation algorithm to develop gridded

cropland fraction data with a spatial resolution of 5¢´5¢. The main

conclusions are as follows: (1) the change in cropland area in five Central

Asian countries between 1000 A.D. and 2000 A.D. had three phases of

"steady with fluctuations - growth - decline". (2) The cropland is

mainly distributed in oases along rivers, with a tendency to expand outward over

time. (3) After 1850 A.D., the increase in cropland area mainly occurred in the

northern part of Kazakhstan. This dataset includes tables of total cropland

area in five Central Asian countries for the last millennium archived in.xlsx

data format and preserved 5¢´5¢ gridded

cropland fractions of five Central Asian countries over the last millennium

archived in.img data format with a data size of 8.61 MB (compressed into one

single file with 422 KB).

Keywords: land use/cover change; cropland

area; gridded allocation; five Central Asian countries

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2022.03.07

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2022.03.07

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset

supporting this paper was published and is accessible through the Digital Journal of

Global Change Data Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2022.04.10.V1 or https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2022.04.10.V1.

1 Introduction

Land

use/cover change (LUCC) has affected natural terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity

as well as has altered the albedo and radiative forcing on the land surface,

which consequently changed global biogeochemical cycles (carbon cycle, nitrogen

cycle, etc.), resulting in far-reaching implications for global climate change[1?C5].

As one of the land use types with the most influential and far-reaching impact

on the original land cover, cropland has been the focus of research regarding

historical land use/cover change. The six existing global- scale historical

land cover datasets (HH[6], SAGE[7], HYDE3.2[8],

PJ[9], LUH[10], KK10[11]) all contain

reconstructions of cropland data.

Reconstruction of relatively accurate

historical cropland cover change based on regional history is one of the

fundamental ways to improve the accuracy of global land cover data[12].

Existing regional reconstructions of historical cropland cover change are

mostly concentra-

ted

in traditional farming regions, such as China[13?C16], Germany[17?C19],

France[20,21], and America[22], while few studies have

been conducted on nonmajor farming regions.

The five Central

Asian countries include Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and

Turkmenistan. Because the five Central Asian countries are landlocked and water

resources are scarce, the majority of this region has been historically

dominated by pastoralism, with only a small amount of cropland in oases around

the Syr Darya and Amu Darya[23]. However, since Tsarist Russia

invaded the five Central Asian countries in the mid-19th century, Kazakhstan??s

agriculture has grown at an astonishing rate in just over 100 years, and

Kazakhstan is now the largest food producer in Central Asia and a major global

food exporter[24]. Therefore, reconstructing the cropland cover

change over the last millennium in five Central Asian countries can not only

help to characterize the spatial and temporal changes in cropland cover in

nonmajor farming regions but also help to understand the impact of

physiogeographic factors associated with human production patterns as well as determine

how humans surpass the limits of physical conditions to exploit land.

This dataset

reconstructed the cropland cover change in five Central Asian countries over

the last millennium based on historical documents. It includes total cropland

area in five Central Asian countries for 25 time sections during 1000-2000 A.D. and 5¢´5¢ gridded cropland cover data for 8 time

sections during 1000-2000 A.D.

The overall goal is for this study to provide a reference for historical

cropland cover reconstruction in nonmajor farming regions.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The

metadata of the Reconstruction dataset of cropland change in five Central Asian

countries over the last millennium (1000-2000)[25] are summarized in Table 1. It includes the

dataset full name, short name, authors, year of the dataset, spatial

resolution, data format, data size, data files, data publisher, and data

sharing policy, etc.

3 Methods

The

development of this dataset consists of the following two main elements: (1) Reconstruction

of cropland area; (2) Gridded allocation. The data sources and references are

shown in Table 2 and Table 3.

3.1 Methods for Reconstructing Cropland Area

The

cropland area for the 13 time sections in this study between 1954 A.D. and 2000

A.D. was obtained directly from the data sources listed in Table 2, and no

direct data sources were available for each time section prior to 1954 A.D. In

these time sections for which no direct data are available, the cropland area

in 1928 A.D. was obtained from statistical yearbooks and historical documents

that combined with the 1954-2000 A.D.

cropland area. The cropland area for the 11 time sections between 1000 A.D. and

1850 A.D. were derived from historical documents and extrapolated back from the

1928 A.D. reconstruction results.

Table 1 Metadata summary of the Reconstruction dataset of cropland

change in five Central Asian countries over the last millennium (1000-2000)

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset

full name

|

Reconstruction

dataset of cropland change in five Central Asian countries over the last

millennium (1000-2000)

|

|

Dataset

short name

|

CroplandCentralAsia_1000-2000

|

|

Authors

|

Jiang,

C. AEN-4274-2022, Beijing Normal University, jayciejiang@mail.bnu.edu.cn

Ye,

Y., Beijing Normal University, yeyuleaffish@bnu.edu.cn

Fang,

X. Q., Beijing Normal University, xfang@bnu.edu.cn

Zhang,

C. P., Beijing Normal University, cpzhang01@163.com

Zhang,

D. Y., Beijing Normal University, zdy2014@mail.bnu.edu.cn

|

|

Geographical

region

|

(Under

modern frontiers) Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and

Turkmenistan

|

|

Year

|

1000-2000A.D.

|

|

Spatial

resolution

|

5¢´5¢

|

|

Data

format

|

.xlsx,

.img

|

|

|

|

Data

size

|

8.61

MB (422 KB after compression)

|

|

|

|

Data

files

|

(1) Data archived in .xlsx

data format includes two tables:

Table 1. Total cropland area

of five Central Asian countries during 1000-2000

Table 2. Cropland area of each

five Central Asian country during 1928-2000

(2) Data archived in .img data

format includes 8 time sections (1000 A.D., 1200 A.D., 1400 A.D., 1500 A.D.,

1750 A.D., 1850 A.D., 1928 A.D., 2000 A.D.) of gridded cropland fraction in

five Central Asian countries

|

|

Foundation

|

Ministry

of Science and Technology of P. R. China (2017YFA0603304)

|

|

Data

publisher

|

Global Change Research Data Publishing &

Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No.

11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data

sharing policy

|

Data from

the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets (in the Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository), and

publications (in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy

includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the

Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to citation;

(3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service providers, are welcome

to redistribute Data subject to written permission from the GCdataPR

Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution license; and

(4) If Data are used to compile new datasets, the ??ten per cent

principal?? should be followed such that Data records utilized should not

surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while sources should be clearly

noted in suitable places in the new dataset[26]

|

|

Communication and searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR, Crossref, DCI, CSCD,

CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

Table 2 Data sources and references for the

reconstruction of cropland area

|

Type of data

|

Data sources and references

|

Time

|

|

Cropland area

|

FAO[27]

|

2000

|

|

Compilation of Economic Statistics of the

Five Soviet Central Asian Republics[28]

Statistical Yearbook of the National

Economy of the USSR 1956[29]

Compilation of Soviet Agricultural

Statistics[30]

Sixty Years of Soviet National Economy[31]

|

1928, 1954, 1955, 1958, 1959, 1962, 1968, 1975, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1983

|

|

Population

|

Atlas of World Population History[32]

|

1000-1850

|

|

Study of Population Issues in Central Asia[33]

|

1750, 1850

|

|

Qualitative description of agricultural

historical facts

|

Outline of Central Asia History[34]

Outline History of Five Central Asian

Countries[35]

General History of Central Asia[36,37]

History of Central Asia[38?C40]

History of Civilizations of Central Asia[41]

History of the Conquest of Central Asia[42]

|

1000-2000

|

|

A History of the Tsarist Russia Conquest of

Central Asia[43]

Soviet Exploitation of Central Asia and

Kazakhstan[44]

Study of the Policy of Russian Rule in

Central Asia[45]

|

1750, 1850, 1928

|

|

Brief History of Central Asia[46]

History of the World Conquer[47]

Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion[48]

The Empire of the Steppes[49]

Turkic Lineage[50]

|

1219, 1229, 1260, 1370, 1400, 1405

|

Table 3 The data sources of gridded allocation

|

Type of data

|

Data sources

|

|

Cultivatable land suitability dataset

|

Zhang??s study[51]

|

|

Cropland fraction data approximately 2000 C.E.

|

Zhang??s study[52]

|

|

Bare land, water bodies, artificial surfaces

|

http://globallandcover.com/home.html?type=data

|

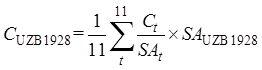

(1) Cropland area in 1928 A.D.

The five Central

Asian countries had data on both cropland area and sown area in the various

statistical yearbooks of the USSR before 1954 A.D., whereas in 1928 A.D., only

data on sown area were available. In terms of the history of agricultural

development in the five Central Asian countries[42?C45], the pattern

of cropland cover in the four Central Asian countries except Kazakhstan has not

changed much in the 20th century. Therefore, the average of the ratio of

cropland area to sown area in 1954-2000 A.D.

can be used instead of the ratio of cropland area to sown area in 1928 A.D. in

these four countries. Equation 1 shows the process of calculating the cropland

area in 1928 A.D. for these four countries using Uzbekistan as an example.

(1)

(1)

where CUZB1928 refers to the cropland area in

Uzbekistan in 1928 A.D.; CUZBt refers to the cropland area in Uzbekistan under

time section t from 1954 A.D. to 2000

A.D., and there are 11 time sections of cropland from 1954 A.D. to 2000 A.D. in

this study; SAUZBt

refers to the sown area in Uzbekistan under time section t from 1954 A.D. to 2000 A.D.; and SAUZB1928 refers to the sown area in Uzbekistan

in 1928 A.D.

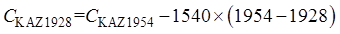

Kazakhstan

experienced rapid large-scale agricultural reclamation in the 20th century that

was extensive and deep, and the ratio of cropland area to sown area in 1928

A.D. cannot be replaced by the average of the ratio of cultivated area to sown

area for the period from 1954 AD to 2000 A.D., as in the other four countries.

Therefore, the cropland area in Kazakhstan in 1928 A.D. was reconstructed

according to historical sources[53], which stated that ??after the

October Revolution, cropland in Kazakhstan increased by an average of 154,000

hectares (converted into 1540 km2) per year??.

(2)

(2)

where CKAZ1928 refers to the cropland area in

Kazakhstan in 1928 A.D. and CKAZ1954 refers to the cropland area in

Kazakhstan in 1954 A.D.

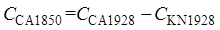

(2) Cropland area

in 1850 A.D.

The agricultural

history of Kazakhstan began with the large-scale agricultural migration from

Tsarist Russia to Kazakhstan in the second half of the 19th century[44]

at the point when Russian migration policy towards Central Asia shifted from a

military based policy to a predominantly agricultural one around the 1860s[45],

which showed a spatial progression from north to south.

Before 1850 A.D.,

agriculture in Kazakhstan was mainly located in the Syr Darya basin in southern

Kazakhstan and near the Zhetysu region in southeastern Kazakhstan. Nomadic

herders predominantly populated the steppes of northern Kazakhstan, with a

negligible cropland fraction, and from 1850 A.D. onwards, the steppes of

northern Kazakhstan experienced large-scale reclamation for cultivation. The

growth of cropland in southern Kazakhstan and the other four countries of

Central Asia during this period is difficult to estimate because of the

difficulty of obtaining population ratios in northern and southern Kazakhstan

from 1850 A.D. to 1928 A.D. and the increased uncertainty created by the

demographic changes brought about by mass migration and changes in population

density resulting from the shift of the nomadic population to the settled population.

However, the cropland fraction in southern Kazakhstan and the other four

countries of Central Asia, although increasing slightly in line with population

growth, is negligible compared to the unprecedentedly large increase in

northern Kazakhstan. Therefore, this study concluded that the increase in

cropland in the five Central Asian countries after 1850 A.D. occurred mainly in

northern Kazakhstan, with the southern part of the five Central Asian countries

reaching the maximum area that could be reached in 1850 A.D. in the context of

this study. This north?Csouth divide in Kazakhstan is derived from An Historical Atlas of Central Asia[54].

The total cropland area of the five Central Asian countries in 1850 A.D. was

calculated by Equation 3.

(3)

(3)

where CCA1850 and

CCA1928 refer to the

total cropland area in the five Central Asian countries in 1850 A.D. and 1928

A.D., respectively, and CKN1928

is the cropland area of northern Kazakhstan in 1928 A.D.

(3) Cropland area

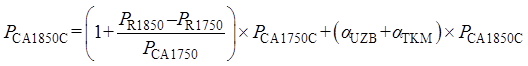

in 1750 A.D.

The rapid

development of irrigation programs in the five Central Asian countries occurred

after 1750 A.D.[40]. A large proportion of the nomadic population

was converted to a settled population and started to engage in farming[35],

which led to the rapid development of cropland area during this period. The

main idea for reconstructing cropland area in 1750 A.D. is shown by Equation 4.

(4)

(4)

where CCA1750 refers to the total cropland

area of five Central Asian countries in 1750 A.D., PCA1850C

refers to the number of people engaged in farming in 1850 A.D., and PCA1750C refers to the number of people engaged in farming

in 1750 A.D.

The population engaged in farming in 1850 A.D. was made up

of two components: the population engaged in farming in 1750 A.D. increased by

the way of natural growth, and the number of people who

switched from pastoralism to farming between 1750 A.D. and 1850 A.D. We

consider the former rate of growth to be equal to the growth rate of the total

population of the region between 1750 A.D. and 1850

A.D. and the latter that the conversion occurred

mainly among the Uzbeks and Turkmens[35, 40]. PCA1750C

was calculated by Equation 5.

(5)

(5)

where PR1850

and PR1750 refer to the total population of the region in 1850

A.D. and 1750 A.D., respectively, and ??UZB and ??TKM refer to the number of Uzbeks and

Turkmens who have switched from pastoralism to farming, respectively, as a

percentage of the total population.

The total

population was derived from the Atlas

of World Population History[32]. The number of the farming

population was converted from the total population combined with the

descriptions in historical sources[34, 35, 55], and the discounted

proportion of the farming population in 1850 A.D. was 60%. The ??UZB and ??TKM are determined from the qualitative

descriptions in references[33, 35, 41-43, 55, 56], with ??UZB at 30% and ??TKM at 8.75%.

(4) Cropland area in 1000 A.D., 1200 A.D., and 1500 A.D.

The period of

rapid cropland development in Central Asia occurred mainly after 1750 A.D.,

before which the total amount of cropland area was small and the development

trend was not positive and tended to be stable[36?C41]. The cropland

area fluctuated only when subject to war or invasion[46?C49], and

such fluctuations are reflected in the reconstruction of cropland area in 1219-1260 A.D. and 1370-1405 A.D.

This study assumed that the per capita cropland area in the five Central Asian

countries during the period 1000-1500

A.D., except for fluctuating time periods, remained the same as in 1750 A.D.

and that the cropland area increased with population growth (Equation 6).

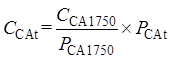

(6)

(6)

where CCAt

refers to the total cropland area in the five Central Asian countries under

time section t that was not affected

by external disturbances during the period 1000-1500 A.D. and PCAt refers to the total population

of the five Central Asian countries under time section t that is not affected by external

disturbances during the period 1000-1500 A.D.

(5) Cropland

area in 1219 A.D., 1229 A.D. and 1260 A.D.

In the year 1219

A.D., Genghis Khan led an invasion of Central Asia, and the arrival of nomads

resulted in a large amount of damage to the cropland in five Central Asian countries[36].

It was not until 1229 A.D. that agriculture began to recover when the cities

and cropland of the region were taken over by Yalavachi[39, 57], and

it recovered to its original level in 1260 A.D.[47]. Therefore, it

can be assumed that the year 1219 A.D. was the start of the disturbance and

1260 A.D. was the end of the disturbance, the cropland area in these two time

sections was unaffected by the disturbance, and the cropland area was

reconstructed in the same way as in Equation 6. The year 1229 A.D. can be considered

the period when the disturbance had its greatest impact and the cropland area

fell to its lowest value during the disturbance, which can be calculated by

Equation 7.

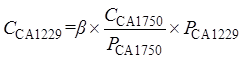

(7)

(7)

where CCA1229 refers to the total

cropland area in the five Central Asian countries in 1229 A.D. and ?? is the

percentage of conversion.

The Mongol invasion of Central Asia resulted in the mass murder of its

inhabitants. As there is a positive correlation between population and cropland

area, ?? can be determined by the

proportion of the population reduced in that period. According to the Empire of the Steppes, approximately

four-fifths of the population was killed, leaving the affairs of the surviving

one-fifth of the population to be managed by Darugachi[49].

Therefore, ?? is taken as 1/5.

(6) Cropland area

in 1370 A.D., 1400 A.D. and 1405 A.D.

In 1370 A.D.,

Timur began his wars of expansion, which had a large impact on agriculture in

five Central Asian countries, similar to the conquest of Genghis Khan. However,

after, and even during, the war of conquest in 1400 A.D., Timur had already

started to recover the economy. Until Timur??s death in 1405 A.D., prosperity

was restored in Central Asia[39]. Therefore, 1370 A.D. was the start

of the disturbance, and 1405 A.D. was the end of the disturbance. The cropland

area in these two time sections was unaffected by the disturbance, and the

cropland area was reconstructed in the same way as in Equation 6. The year 1400

A.D. can be considered the period when the disturbance had its greatest impact and

the cropland area fell to its lowest value during the disturbance, which can be

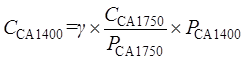

calculated by Equation 8.

(8)

(8)

where CCA1400 refers to the total

cropland area in the five Central Asian countries in 1400 A.D. and ?? is the

percentage of conversion.

The Timurid

leaders continued the Mongol nomadism of Genghis Khan??s time and their

systematic means of destruction[49], with the intention of emulating

their ancestors. Therefore, this study concludes that the damage to the

cropland of five Central Asian countries during the Timurid period is

comparable to that of the Genghis Khan period, which means that ?? has the same value as ?? and is also taken as 1/5.

3.2 Methods for Allocating Historical

Cropland Area into Grid Cells

In

the gridded allocation of cropland area in the five Central Asian countries,

country-specific data are available for the cropland area in 1928 A.D. and 2000

A.D., so the ??study units?? used for the distribution of these two sections are

for each of the five Central Asian countries (which means there are five study

units). The total cropland area for the 1850 A.D. and earlier sections is only

available for the five Central Asian countries as a whole, so the ??study unit??

used for these sections is the five Central Asian countries as a whole (which

means there is only one study unit).

In this study, based on the gridded cultivatable land suitability

data calculated by Zhang et al.[51],

the gridded allocation of cropland was completed through the following steps.

(1) Creating 5¢´5¢ resolution grids covering five Central

Asian countries. The cropland fraction in 2000 A.D. calculated by Zhang et al.[52] was summed with

the fraction of ??Artificial Surface?? in the GlobeLand30 dataset in 2000 A.D. on

a 5¢´5¢ grid as the potential cropland fraction of the grids in 2000 A.D.

(Equation 9). The grids were ranked in order of potential cropland fraction

from higher to lower and then divided into 10 equal parts in the number of

grids covering the study units from higher to lower fraction.

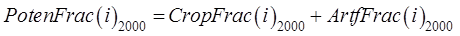

(9)

(9)

where

PotenFrac(i)2000 refers to the potential cropland fraction in the ith grid cell; CropFrac(i)2000 is the cropland fraction in the ith grid cell in 2000 A.D.;

and ArtfFrac(i)2000 is the

fraction of the artificial surface in the ith

grid cell.

(2) The area of a

grid with a resolution of 5¢´5¢ varies with latitude, so grids with

the same cropland fraction may actually have different cropland areas. To

eliminate the error introduced by this problem, the area of the grids in the

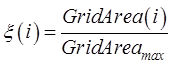

study units needed to be corrected by Equation 10.

(10)

(10)

where

??(i) refers to the grid area correction

factor in the ith grid

cell; GridArea(i) refers to the grid

area in the ith grid cell;

and GridAreamax refers to

the largest grid area in the study unit to which the ith grid cell belongs.

(3) In this study,

the percentage of cultivable land for a 5¢´5¢ resolution grid cell was assumed to be

90%. Allocated the cropland area in the first decile grids according to

Equation 11 and set the percentage of cultivable land of the first decile grids

at 9%.

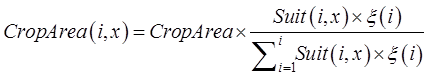

(11)

(11)

where CropArea(i,x) refers to the

cropland area that has been allocated in the ith grid cell in allocation unit x; CropArea is the total

area of cropland in the study unit; Suit(i,x)

refers to the gridded cultivatable land suitability data in the ith grid cell in allocation

unit x; and??(i) refers to the grid area correction factor in the ith grid cell.

(4) If at the end

of the allocation for the first decile girds there was still a surplus of

cropland area, the allocation for the second decile grids began in accordance

with Equation 11 with the percentage of cultivable land at 9%, and at the same

time the allocation for the first decile girds continued in accordance with

Equation 11 with the percentage of cultivable land at 18%. Following the above

rules, the cropland could be allocated to all deciles by iteration. If all the

cropland area of the study unit was allocated, the allocation stopped, and if

there was still a surplus of cropland area in the study unit at the end of the

allocation in the 10th decile girds, the remaining cropland area was allocated

throughout the study units in accordance with Equation 11.

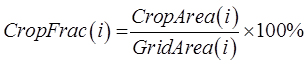

(5) Cropland

fraction calculation (Equation 12).

(12)

(12)

where

CropFrac(i) refers to the cropland fraction of the ith grid; CropArea(i) is the cropland area of the ith grid; and GridArea(i) is the area of the ith grid.

(6) Correction

of oversaturated grids.

1) This study considered water bodies and bare land

to be noncultivable land, whereas the extent of modern nascent water (mostly

reservoirs) could be regarded as historically cultivable land; therefore, the

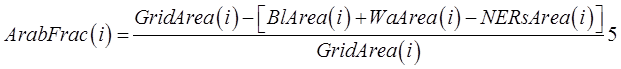

arable land fraction in the grid could be calculated by Equation 13.

(13)

(13)

where

ArabFrac(i) refers to the arable

land fraction in the ith

grid; GridArea(i) refers to the area of the ith grid, BlArea(i) refers to the bare land area in the ith grid, WaArea(i) refers to the water body area in the ith grid and NERsArea(i) refers to the modern nascent water area in the ith grid obtained from

natural earth data.

2) Combining the

percentage of cultivable land for a 5¢´5¢ resolution grid cell (90% in this

study) and the arable land fraction in the grid (Equation 13), the maximum

cropland fraction in the grids could be calculated by Equation 14.

(14)

(14)

where

CropFracmax(i) refers

to the maximum cropland fraction in the ith

grid and ArabFrac(i) refers to the arable land fraction in the ith grid.

For the grids

where CropFrac(i) exceeded CropFracmax(i), CropFracmax(i) was directly assigned

as their CropFrac(i) and summed up all the excess grids??

cropland area and reallocated them to the grids that did not reach their CropFracmax(i) according to Equation 11. This step was

repeated several times until all grids?? CropFrac(i) values were lower than CropFracmax(i), and the correction ended.

4 Data Results and Validation

4.1 Data Composition

The

reconstruction dataset of cropland change in Five Central Asian countries over

the Last Millennium (1000-2000)

contains the total cropland area of five Central Asian countries during 1000-2000 A.D. and the 5¢´5¢ gridded cropland fraction of five Central

Asian countries during 1000-2000 A.D.

The cropland area for 25 time sections include 2 tables of the total cropland

area of five Central Asian countries during 1000-2000 and the cropland area of each of the five Central Asian

countries during 1928-2000,

which are archived in.xlsx data formats. The gridded cropland fraction with a

spatial resolution of 5¢´5¢ includes 8 time sections (1000 A.D.,

1200 A.D., 1400 A.D., 1500 A.D., 1750 A.D., 1850 A.D., 1928 A.D., 2000 A.D.),

which are archived in .img data formats.

4.2 Data Products

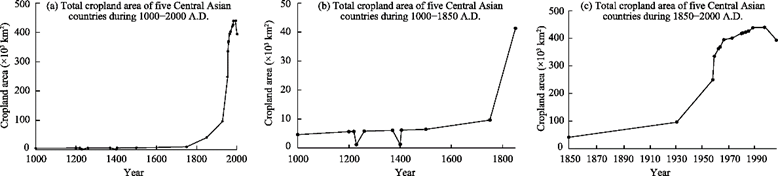

Changes

in total cropland area in five Central Asian countries during 1000-2000 A.D. are shown in Figure 1. The change in cropland area over

the last millennium in the five Central Asian countries can be divided into

three phases: a smooth phase with fluctuations from 1000 A.D. to 1750 A.D., a

rapid increase from 1750 A.D. to 1992 A.D., and a decline from 1992 A.D. to

2000 A.D.

The total

cropland area in the five Central Asian countries was 9,617.46 km2 in 1750 A.D., before which the total cropland area did not change much,

and the cropland area increased slowly with population growth. However, there

were fluctuations in cropland area caused by warfare in the early 13th and late

14th centuries, causing the cropland area to fall to 1,229.57 km2 in

1400 A.D. and to 1,137.98 km2 in 1229 A.D.

Cropland in

Central Asia grew rapidly between 1750 A.D. and 1992 A.D. In particular, the

cropland area increased from 41,329.87 km2 to 439,780 km2 between 1850 A.D. and

1992 A.D., which represented a nearly tenfold increase

over more than 100 years. This was the result of Tsarist Russia??s large-scale

land reclamation in Central Asia, especially in Kazakhstan.

Between 1992

A.D. and 2000 A.D., the cropland area decreased significantly from 439,780 km2

in 1992 A.D. to 394,323 km2 in 2000 A.D. This is due to the

destruction of agriculture as a result of the change in policy regimes in five

Central Asian countries after the dissolution of the Soviet Union[58].

Particularly in Kazakhstan, the loss of a large number of farmers and capital

from the countryside has led to large-scale abandonment of cropland.

Figure

1 Total cropland

area of five Central Asian countries during 1000-2000 A.D.

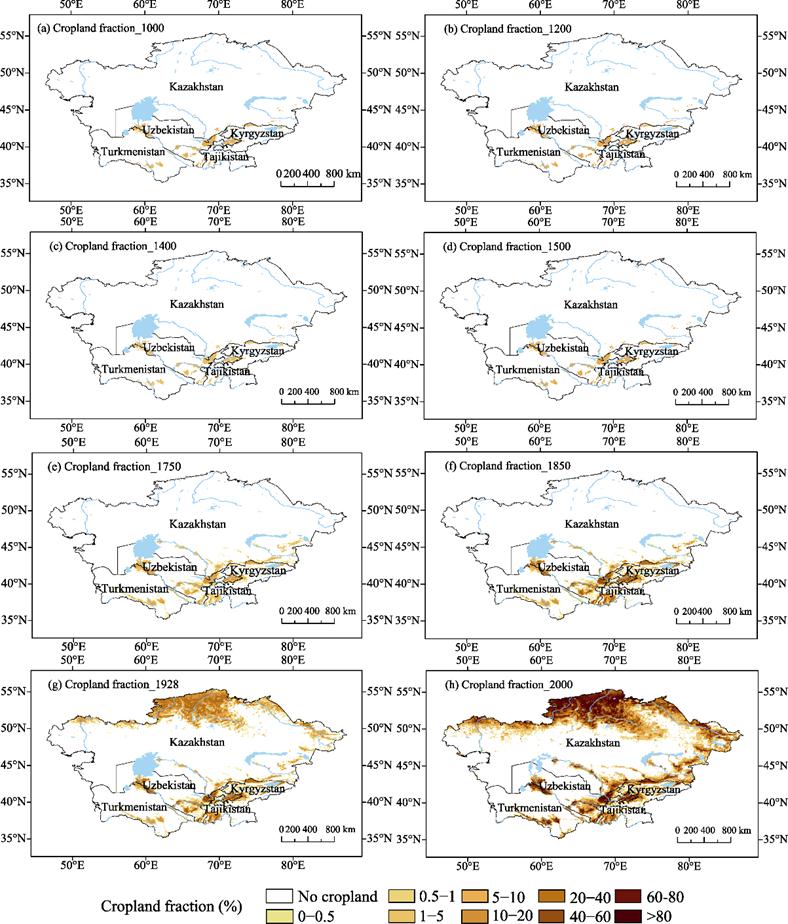

The 5¢´5¢ gridded cropland fraction in Central

Asia during 1000-2000 A.D. is shown in Figure 2. The

cropland was mainly distributed in oases around the Amu Darya and Syr Darya in

southern Central Asia, such as the Khorezm Oasis, Fergana basin in Transoxiana,

Zeravshan River valley oases, which nourish Samarkand and Bukhara, and Merv

Oasis and Akhal Oasis in Turkmenistan. Cropland was also distributed in the Talas

River basin, the Chu River basin, and the Zhetysu region. One of the

distinctive features of the distribution of cropland in Central Asia was the

distribution along rivers. This is due to the aridity and lack of rainfall in

Central Asia, where rivers are an important source of irrigation water. In Central

Asia, agriculture can be developed only when water sources and irrigation

systems are available.

Over time, there

has been a tendency for cropland to expand outwards from the oasis. Especially

since 1750 A.D., there has been a rapid increase in cropland area and a marked

increase in the extent of expansion. Selecting 1850 A.D. as a turning point,

the distribution of cropland in Kazakhstan changed significantly. With the

invasion of Tsarist Russia, large-scale migration and reclamation activities in

northern Kazakhstan led to a rapid expansion of the cropland from north to

south. Kazakhstan was transformed from a pastoralist country to an agricultural

power in just 100 years, and it finally became the breadbasket of the Soviet

Union.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

This study reconstructed the total

cropland area and 5¢´5¢ gridded cropland fraction in five

Central Asian countries during 1000-2000 A.D.

The main conclusions are as follows: (1) The change in cropland area in five

Central Asian countries between 1000 A.D. and 2000 A.D. had three phases of

??steady with fluctuations-growth-decline??. (2) Cropland was

Figure

2 The 5¢´5¢

gridded cropland fraction in Central Asia during 1000-2000 A.D.

mainly

located in oases along the rivers and tends to expand outwards over time. After

1850 A.D., the increase in cropland area occurred mainly in the northern part

of Kazakhstan. The reconstruction of cropland cover change in five Central

Asian countries in the last millennium can provide ideas for the reconstruction

in nonmajor farming regions where data sources are less available and help to

compare the spatial and temporal characteristics of cropland development in

major farming regions and the region else.

Author Contributions

Ye, Y. and Fang, X. Q.

designed the algorithms of the dataset. Jiang C. contributed to the processing

and analysis of the cropland area. Zhang C. P. designed the gridded allocation

algorithm. Zhang C. P. and Zhang, D. Y. provided guidance and advice on the gridded

allocation algorithm. Jiang C. wrote the data paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]

Ruddiman, W. The anthropogenic

greenhouse era began thousands of years ago [J]. Climatic Change, 2003, 61(3): 261‒293.

[2]

Pielke, R., Pitman, A., Niyogi,

D., et al. Land use/land cover

changes and climate: modeling analysis and observational evidence [J]. WIREs Climate Change, 2011, 2(6):

828‒850.

[3]

Zhang, X., Wang, W., Fang, X., et al. Agriculture development-induced

surface albedo changes and climatic implications across northeastern China [J].

Chinese Geographical Science, 2012,

22(3): 264‒277.

[4]

Crossman, N., Bryan, B., de

Groot, R., et al. Land science

contributions to ecosystem services [J]. Current

Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2013, 5(5): 509‒514.

[5]

Gaillard, M., Morrison, K.,

Madella, M., et al. Past land-use and

land-cover change: the challenge of quantification at the subcontinental to

global scales [J]. Past Global Change

Magazine, 2018, 26(1): 3.

[6]

Houghton, R., Hobbie, J.,

Metillo, J. Changes in the carbon content of terrestrial biota and soils

between 1860 and 1980: a net release of CO2 to the atmosphere [J]. Ecological Monographs, 1983, 53(3):

235‒262.

[7]

Ramankutty, N., Foley, J.

Estimated historical changes in global land cover: croplands from 1700 to 1992

[J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles,

1999, 13(4): 997‒1027.

[8]

Klein Goldewijk, K., Beusen,

A., Doelman, J., et al. Anthropogenic

land use estimates for the Holocene??HYDE 3.2 [J]. Earth System Science Data, 2017, 9(2): 927‒953.

[9]

Pongratz, J., Reick, C.,

Raddatz, T., et al. A reconstruction

of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium [J]. Global biogeochemical cycles, 2008,

22(3): GB3018.

[10]

Hurtt, G., Chini, L., Frolking,

S., et al. Harmonization of land-use

scenarios for the period 1500?C2100: 600 years of global gridded annual

land-use transitions, wood harvest, and resulting secondary lands [J]. Climatic Change, 2011, 109(1): 117‒161.

[11]

Kaplan, J., Krumhardt, K.,

Ellis, E., et al. Holocene carbon

emissions as a result of anthropogenic land cover change [J]. Holocene, 2011, 21(5): 775‒791.

[12]

Fang, X., Ye, Y., Zhang, C., et al. Cropland cover change and its

environmental impacts in the history of China[J]. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2019, 21(1): 160‒173.

[13]

Ge, Q., Dai, J., He, F., et al. Change of the amount of cropland

resource and analysis of driving forces in partial provinces in China during

the past 300 years [J]. Progress in

Natural Science, 2003, 13(8): 825‒832.

[14]

Lin, S., Zheng, J., He, F. The

approach for gridding data derived from historical cropland records of the

traditional cultivated region in China [J]. Acta

Geographica Sinica, 2008, 63(1): 83‒92.

[15]

Ye, Y., Fang, X., Ren, Y., et al. Cropland cover change in

Northeast China during the past 300 years [J]. Scientia Sinica Terrae, 2009, 39(3): 340‒350.

[16]

Wei, X., Ye, Y., Zhang, Q., et al. Reconstruction of cropland change

over the past 300 years in the Jing-Jin-Ji area, China [J]. Regional Environmental Change, 2016,

176(8): 1‒13.

[17]

Bork, H., Bork, H., Dalchow,

C., et al. Landschaftsentwicklung in

Mitteleuropa [M]. Wirkungen des Menschen auf Landschaften. Gotham: Klett, 1998.

[18]

Haase, D., Walz, U., Neubert,

M., et al. Changes to Central

European landscapes??analysing historical maps to approach current environmental

issues, examples from Saxony, Central Germany [J]. Land Use Policy, 2007, 24(1): 248‒263.

[19]

Jansen, F., Zerbe, S., Succow,

M. Changes in landscape naturalness derived from a historical land register??a

case study from NE Germany [J]. Landscape

Ecology, 2008, 24(2): 185‒198.

[20]

Girel, J., Vautier, F., Peiry,

J. Biodiversity and Land Use History of the Alpine Riparian Landscapes (The

Example of the Isere River Valley, France) [M]//Multifunctional Landscapes, Vol.

III: Continuity and Change. Southampton (eds. Mander, Ü., Antrop, M.). Wit Press,

2003: 167?C200.

[21]

Delile, H., Schmitt, L.,

Jacob-Rousseau, N., et al. Headwater

valley response to climate and land use changes during the Little Ice Age in

the Massif Central (Yzeron basin, France) [J]. Geomorphology, 2016, 257: 179‒197.

[22]

Etter, A., McAlpine, C.,

Possingham, H. Historical patterns and drivers of landscape change in Colombia

since 1500: a regionalized spatial approach [J]. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 2008, 98(1):

2‒23.

[23]

Stroyev, ??. ??. Physical

Geography of the USSR [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1960.

[24]

Qu, C., Zhang, Z. Overview of

agricultural development in Kazakhstan [J]. World

Agriculture, 2014(2): 145‒148.

[25]

Jiang,

C., Ye, Y., Fang, X., et al.

Reconstruction dataset of cropland change in five Central Asian countries over

the last millennium (1000-2000) [J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2022.04.10.V1. https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2022.04.10.V1.

[26]

GCdataPR Editorial Office.

GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL]. https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy. 2014.05

(Updated 2017).

[27]

FAO. FAOSTAT [EB/OL].

2001[2020-11-17]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/.

[28]

Institute

of Central Asian Studies of Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences. Compilation of

Economic Statistics of the Five Soviet Central Asian Republics [M]. Urumqi:

Xinjiang Academy of Social Sciences, 1983.

[29]

Editorial Department of

Statistics Press. Statistical Yearbook of the National Economy of the USSR 1956

[M]. Beijing: Statistics Press, 1957.

[30]

Li, R. Compilation of Soviet

Agricultural Statistics [M]. Beijing: Agriculture Press, 1981.

[31]

Central Bureau of Statistics of

the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union. Sixty Years of Soviet National

Economy [M]. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 1979.

[32]

McEvedy, C., Jones, R. Atlas of

World Population History [M]. Beijing: The Eastern Publishing, 1992.

[33]

Wu, H. Study of Population

Issues in Central Asia [M]. Beijing: Minzu University of China Press, 2004.

[34]

Ivanov, P. Outline of central

Asia history [J]. Central Asia Series,

1983, 1:15‒124.

[35]

Ma, D., Feng, X. Outline

History of Five Central Asian Countries [M]. Urumqi: Xinjiang Peoples??s Rublishing

House, 2005.

[36]

Wang, Z. General History of

Central Asia (Volume of Ancient ??) [M]. Beijing: Peoples??s Rublishing House, 2010.

[37]

Wang, Z. General History of

Central Asia (Volume of Modern Times) [M]. Beijing: Peoples??s Rublishing House,

2010.

[38]

Lan, Q., Liu, R. History of

Central Asia (Volume 3) [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2018.

[39]

Lan, Q., Liu, G. History of

Central Asia (Volume 4) [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2018.

[40]

Lan, Q. History of Central Asia

(Volume 5) [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2018.

[41]

Adle, C., Habib, I. History of

Civilizations of Central Asia (Volume 5: Development in Contrast, from the

Sixteenth to the Mid-nineteenth Century) [M]. Beijing: China Translation &

Publishing Corporation, 2006.

[42] Terentyev, M. History of the Conquest

of Central Asia (Volume 3) [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1986.

[43]

Wu, Z. A History of the Tsarist

Russia Conquest of Central Asia [M]. Guiyang: Guizhou Educational Publishing

House, 1996.

[44]

Zhang, B. Soviet Exploitation

of Central Asia and Kazakhstan [M]. Urumqi: Xinjiang Peoples??s Rublishing

House, 1989.

[45] Meng, N. Study of the Policy of Russian

Rule in Central Asia [M]. Urumqi: Xinjiang University Press, 2000.

[46]

Barthold, V. Brief History of

Central Asia [M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005.

[47]

Juvaini. History of the World

Conquer [M]. Hohhot: Inner Mongolia Peoples??s Rublishing House, 1980.

[48] Barthold, V. Turkestan Down to the

Mongol Invasion [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, 2011.

[49]

Grousset, R. The Empire of the

Steppes [M]. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1999.

[50]

Abul-Ghazi, B. Turkic Lineage

[M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005.

[51]

Zhang, C. P., Ye, Y., Fang, X.

Q. Global cultivatable land suitability dataset based on physical-geographic factors

[J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global

Change Data Repository, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb. 2022.04.01.V1.

https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2022.04.01.V1.

[52]

Zhang, C. P., Ye, Y., Fang, X.

Q., et al. Synergistic modern global

1 km cropland dataset derived from multi-sets of land cover products [J]. Remote Sensing, 2019, 11(19): 2250‒2268.

[53]

Zhang, B. How Kazakhstan was

turned into a Soviet breadbasket [J]. World

Agriculture, 1983(3): 53‒55.

[54]

Bregel, Y. An Historical Atlas

of Central Asia [M]. Boston: Brill, 2003.

[55]

Wang, Z. Modern History of

Central Asia: 16-19 Century [M]. Lanzhou: Lanzhou

University Press, 1989.

[56]

Hu, Y. A preliminary study of

the relations between the Khohan Khanate and the Kyrgyz in the eighteenth and

nineteenth centuries [J]. Journal of

Lanzhou University, 1991(2): 54‒61.

[57]

Chen, G. On the two Muslim

statesmen of the West during the Mongol rule: Yalavachi and Maskhut [J]. North West Ethno-national Studies, 1995,

(1): 137‒145.

[58] Li, Z. Agriculture in Central Asia:

reality and future [J]. Former Soviet

Union and Eastern Europe Today, 1993, (3): 34‒36.