The Content and Composition of Dataset of Wei, Chun and Wei,

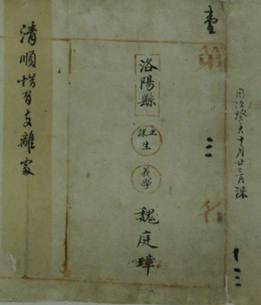

Tingzhang??s Imperial Examination Papers Archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents

Museum

Xu, N. H.

Luoyang Folk Museum, Luoyang

471000, China

Abstract: The dataset of Wei,

Chun and Wei, Tingzhang??s Imperial Examination papers archived by Luoyang

Indenture Documents Museum included 74 Imperial Examination papers of Wei, Chun

and Wei, Tingzhang in Luoyang county, Henan prefecture

in the late Qing dynasty. These examination papers were from Daliang Academy, Luoyang

County Academy and Zhounan Academy. The examination places were mainly in Luoyang

county, Henan Prefecture in the Qing dynasty. The

examination content was a typical traditional formation called eight-part

essay. The dataset was developed based on the datasets of the Luoyang Indenture

Documents Museum. The dataset includes: (1) digital pictures of 74 Imperial

Examination papers in the late Qing dynasty (including 13 Wei, Chun??s and 61

Wei, Tingzhang??s test papers), and each file was named after the archive code;

(2) the statistics of the Imperial Examination papers, including ID, title,

tile source, archive code, size, material, dynasty, number, style and ranking.

The dataset is archived in .jpg and .xls data formats, and consists of 75 data

files with data size of 340 MB (compressed into one file with 335 MB).

Keywords: Wei,

Chun; Wei, Tingzhang; Imperial Examination papers; Imperial Examination System;

late Qing dynasty

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2021.04.09

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2021.04.09

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset

supporting this paper was published and is accessible through the Digital Journal of Global Change Data

Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.07.02.V1 or

https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.07.02.V1.

1 Introduction

The Luoyang Folk Museum features a dataset of Imperial

Examination papers archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum in the late

Qing dynasty, which number 74 authored by Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z. in Luoyang county, Henan province. Written in the typical style of

Baguwen or the eight-part essay, these papers are so rare that they are of good

use for studying the Imperial Examination and even the education system in the

middle and late Qing dynasty.

These papers had been collected by a local before 2010 who

resided in Laocheng of Luoyang. According to the collector??s research, Wei, C.

and Wei, T. Z. were father and son. As the rare historical documents, they have

provided us with the historical evidence for getting insight into the Imperial

Examination and education system in the late Qing dynasty.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The metadata of the dataset of Wei, Chun and Wei, Tingzhang??s

Imperial Examination papers

archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum[1]

is summarized in Table 1. It includes the dataset full name, short name,

author, year of the dataset, data format, data size, data files, data

publisher, and data sharing policy, etc.

Table 1 Metadata summary of the Dataset of Wei,

Chun and Wei, Tingzhang??s Imperial Examination papers archived by Luoyang

Indenture Documents Museum

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset

full name

|

The

dataset of Wei, Chun and Wei, Tingzhang??s Imperial Examination Papers

Archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum

|

|

Dataset

short name

|

WeiChun&WeiTingzhang_Papers

|

|

Author

|

Xu, N.

H., Luoyang Folk Museum, 496034994@qq.com

|

|

Geographical

region

|

Luoyang

of Henan province; Kaifeng prefecture

|

|

Year

|

Qing dynasty

(1636–1912); Tongzhi period of Qing dynasty

|

|

Data

format

|

.jpg, .xls

|

|

Data

files

|

75

|

|

Data

size

|

340 MB (Compressed to 1 file, 335 MB)

|

|

Data

publisher

|

Global Change Research Data Publishing &

Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No.

11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data

sharing policy

|

Data from

the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes dataset, datasets (in

the Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository), and

publications (in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy

includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the

Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to

citation; (3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service

providers, are welcome to redistribute Data subject to written permission

from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution

license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new

datasets, the ??ten per cent principal?? should be followed such that Data

records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while

sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[2]

|

|

Communication and searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR, Crossref, DCI,

CSCD, CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

3 Contents of the Dataset

The dataset was developed based on the collections of the

Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum, a collection of Imperial Examination papers

in the late Qing dynasty, which number 74 authored by Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z. in

Luoyang county, Henan province. The Dataset includes: ID; name; picture; title

source; archive coding; size; material; dynasty; number; style; the imperfect

of paper; ranking. In view that some papers are incomplete, we can??t specify

the exact time, rankings and some others. However, due to the father-son

relationship between Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z., it can be concluded that the

papers were dated around the late Qing dynasty (Tongzhi period of Qing dynasty)

due to what were written on some papers including Baguwen or the eight-part

essay, and examination poem.

The answer sheet of Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z. in the late Qing

dynasty filed in Luoyang Museum of Contract Documents is made in

Chinese art paper or Xuan paper, with some printed with small square

lattices which will avail the examinees of brush writing in regular script. The

exam papers are officially stamped with the seal engraved in Manchu and Chinese

in red script character. Most of the examination papers are used for the

preliminary model tests either held in schools or organized by the government

in preparation for the province-level examination.

3.1 Official and Unofficial

Schooling

Most papers archived in this dataset are used for the

official and unofficial simulated examinations, and some are papers for the

province-level examination. The official schooling and unofficial schooling,

supplementary to each other, both played an important role in the Qing dynasty

when the Imperial Examination System prevailed. The official schooling refers

to the teachings of textbooks approved by the imperial court including ??Four

Books and Five Classics??, which look unchanged in terms of the contents.

In particular, the Four Books must be compulsory for every student since they

entered school. However, the unofficial schooling offered by the academy of

classical learning may differ from one to another, mainly including the

mainstream knowledge of philosophical writings and miscellaneous works, the

textual research, rhetoric and craftsmanship. The official schooling serves the

purposes of training local students to pass the province-level examination

while the academy of classical learning mainly focuses on training academic

talents but not on providing some exam-oriented training. The state-run

school is fully funded by the government while the income of classical learning

academy mainly comes from government grants, donations from gentry and

self-management income.

In the late Qing dynasty, most academies of classical

learning became examination- oriented, aiming at passing the Imperial

Examinations by improving students?? performance in writing Baguwen. The model

examinations organized by these academies are always held on a regular basis

and strictly carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Imperial

Examination, with a set of procedures such as exam question preparing, testing,

examination monitoring, grading, rewarding, punishing and so on. The

examination either supervised by local governmental official or the academy

president, is generally based on Baguwen or the eight-part essay. The model

testing would be conducted for several times every month in the exam-oriented

academy rather than teaching and grading students. Those who excel in the

examination will be rewarded, while those who poorly performed will be

criticized. It should be pointed out that students in exam-oriented academy are

generally graduates of government-run schools who are always very capable of

passing the examination.

These exam papers of Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z. come from the

educational institutions, including Daliang Academy, Luoyang County School and

Zhounan Academy. Located in Daliang (today??s Kaifeng), the capital of Henan

province, Daliang Academy was the highest-level institution in Henan, and one

of the top in the country. Many students felt honored to study in Daliang

Academy and became closer to their officialdom if they won the title of Jinshi,

the successful candidate in the highest-level civil

servant examinations. Situated in Luoyang county,

Zhounan Academy had a better education resources and performance than other

preliminary academy in that period. Most of Wei, C.??s papers come from Daliang

Academy while Wei, T. Z.??s are mostly from Luoyang County School and a few from

Zhounan Academy. The father Wei, C. performed better than his son Wei, T. Z. in

terms of schools where they studied (Daliang Academy out-ranked Luoyang County

School and Zhounan Academy).

3.2 Most Archived Papers

for the Preliminary Imperial Examination

To pass the preliminary examination can only help the

attendees to obtain the qualification for the Imperial Examination. In the

literature of Qing dynasty, those disciplines which were not marked as martial

arts all referred to the liberal arts, the mainstream subject for

selecting candidates for officialdom. Once the attendees passed the

preliminary examination, they can go further to attend the province-level

examination, ministry-level examination and the emperor until

their names were put on the published list of successful

candidates[3]. The preliminary

examination in Qing dynasty was held twice in three years, further classified

into county-level test, prefecture-level test and the test under the

supervision of provincial education commissioner. Most of Qing dynasty papers

filed by Luoyang Contract Documents Museum are for the preliminary examination,

which can be demonstrated by the many terms just like candidates?? identities

(students for major and minor courses), rankings (top-grade class, super-class

and first-class).

An Imperial Examination paper from right to left are in

order as follows, exam time, ranking (top-grade class, super-class and

first-class, major courses), candidates?? status (birthplace, name), comments,

title and body (prose and poetry). The test paper No.029792 is exemplified

below.

In the 2nd year of the Sexagenary

Cycle, Wei, T. Z., a local of Luoyang county, ranked 16th among all

Zhengke students. He did

well in reasoning to the point and being good at planning and able to complete

tasks with prudence; main body.

|

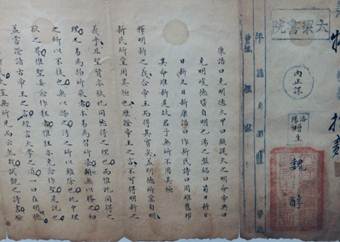

Figure 1 The province-level examination of Wei, C. (part of 024620)

|

|

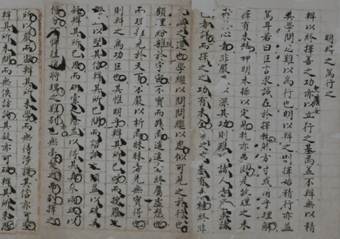

Figure 2 The province-level examination of Wei, T. Z. (part of 028946)

|

As for Zhengke, it is pointed out in history of ancient

Chinese education that Zhengke students refer to undergraduates who study

courses in the academy of classical learning and generally fall into Zhengke,

Fuke, in-class Neike and other categories based on their test scores or whether

they live in school or not. In rules of Yanping Academy selected from volume 12

of Changping state records write ??there are students of top-grade class,

super-class and first-class while the students that passed the preliminary exam

should be classified into excellent,

superior and secondary ones...In the very beginning of the academic

year, we would examine and decide on who would be granted the top-grade status

of Zhengke, Fuke and Waike, with the subsidies ranging from 1,200 to 600 and to

none per person; the excellence status of Zhengke, Fuke and Waike, with the

subsidies ranging from 600 to 300 and to none per person??[4]. Such

subsides can rise and fall according to whether the students should take the

test or not and whether their grades are good or bad.

From the examination papers of Wei, C. and Wei, T. Z. who

won the Zhengke status, there are a variety of status, including the top-grade

class, super-class and first-class as well as other rankings. From the writing

of Zengsheng in the test paper and the classification of the status, it can be

seen that Wei, C. was a Zengsheng while Wei, T. Z. was a Shengyuan, a student

who has the qualification to participate in the province-level examination.

Therefore, these documents of Wei, T. Z. must be test papers for the

preliminary examination.

3.3 Baguwen or the Eight-part

Essay and Test Poem

Wei, T. Z.??s papers in the dataset are typical of Baguwen

or eight-part essay. The titles are always originated from

the Four Books of the Great Learning, with more than

thirty selected from the Analects of Confucius, about ten from

Mencius, three from the Doctrine of the Mean and three from the Great

Learning. Generally speaking, these test questions from these papers are

written in the person of Confucius, Mencius and other saints through the full

text, composed of eight parts, namely, Poti, Chengti , Qijiang, Ruti, Qigu,

Zhonggu), Hougu, Shugu . Discourse on politics is followed by test poem in the

form of ??ode to??, then to??, mostly with five words and eight rhymes, and a few

with five words and six rhymes.

Baguwen

or the eight-part essay is always composed of 800 words in discussion of

current politics, government affairs and other related issues. The examinee??s

personal opinions on the topic should be explained on the basis of theories in

the Four Books, with the small characters written in regular script.

For example, the test paper numbered 028923 is the only answer sheet which

contains ??one essay, one ode and one poem??. The title is ??Distinguishing and

Practice Earnestly??, which comes from ??Book of Rites-Doctrine of the

Mean??, and the body begins with:

Distinguishing

the right from the wrong can help one to seek for the merits while one??s

practice would finally work. With no distinguishing the right from wrong,

one can??t be knowledgeable, let practice alone. If one distinguishes well, he

can find the essence at the beginning and practice much better in the end (i.e.,

Poti, opening the topic).

The

following is the expression of the examinee??s personal opinions:

According

to the words of Confucian scholar, to seek for earnest practice lies in

choosing good deeds and doing them persistently. However, there is

understandings and misinterpretation even for the immortal. To choose good

deeds and persist in doing is undoubtedly the point (with no marks punctuated

in the examination papers).

The title of Fu literature is ode to the inauguration of

exam courtyard pleasing the come-down scholars, with the writing more than 600

words done in antithesis sentences. The examinees should tell what good it will

bring to them and express their gratitude after the completion of the

courtyard.

|

Figure 3 The examination of Wei, T. Z. (part of 028923)

|

At the beginning of the paper is a comment, saying the

writing is natural in the style and rich in the structural expressions while

the deficiencies lie in the conclusion and poem. It is an overall evaluation of

the whole article in terms of its writing, Fu literature and poem, pointing out

the merits like the sense of hierarchy, and demerits such as the lack in the

warning strategies and the improper composition of the poem.

This is a relatively complete test paper, which explores

the relationship between learning and practice, and how to use the knowledge in

practice. Except this test paper, other papers are provided with one article

and one poem but no Fu literature, which may be related to the directions of

the examination in terms of the content or the examination level.

Secondly, most of these papers (except for incomplete

papers) have exam poems written in the ending. As a poetic style, the exam poem

is also called Fude style in Fu literature (it has its fixed format: Fude??De??),

mainly used in Imperial Examination. The poem always has the title selected

from the verses of famous poets or idioms and in Fude style, with each line

written in five words and six rhymes or eight rhymes. The strict requirements

rest in the exact number of rhymes and the relevance to the title. In the exam

poem of Wei, T. Z.??s paper filed in the museum is posted with many lines of

ancient poets.

Composing poem as one part of Imperial Examinations did not

begin in Qing dynasty but originated in Tang dynasty. In the Imperial Examinations

in Tang and Song dynasties, the exam poem is also called Tang Rhyme, in which

the four rhymes and six rhymes but not eight rhymes are generally used. It is

one of the important part for Imperial Examination from Tang dynasty to the early Song dynasty

until Wang, Anshi ordered to call off the exam poem in Imperial Examination

during the Songshenzong period, so did in Yuan and Ming dynasties. Since the

Qianlong period of Qing dynasty, the use of exam poem was gradually restored,

with five-character and eight-rhyme poem required for province-level and

ministry-level exams. However, it has such an increasingly strict restriction

in the form just as the fixed format in Baguwen or the eight-part essay. The

titles always selected from the philosophical writings and miscellaneous works

of the Confucian school, the verses of famous poets or idioms, the poem is

required to be written in Fude style and ended with praising the merits and

virtues of the emperor. Each line of Wei, T. Z.??s exam poem was mostly written

in five words and in six rhymes or eight rhymes, with a few lines in five words

and six rhymes.

3.4 Difficulty in Passing the

Imperial Examination Evidenced by Wei, T. Z.??s Examination Papers

Among the archived Imperial Examination papers, there are

62 papers belonging to Wei, T. Z., ranking the top-grade class, the super-class

and the first-class respectively. In spite of no known information of Wei, T.

Z.??s lifetime, it can be seen that he has participated in the examination many

times from the second year to the tenth year of emperor Tongzhi and provided

dozens of exam papers, which tell us how difficult to pass the Imperial

Examination .

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, candidates

who passed the county-level and the prefecture-level examination in the

preliminary examination could won the title of

Tongsheng, which can prove that the winner is capable of reading, examining and

writing. However, many a scholar was still a Tongsheng when their hair turned

pale. For example, according to Unofficial history of

officialdom authored by Wu, Jingzi, Fan, Jin sat for exam for Juren at the age of 20, and succeeded at 54,

which proved to be a happy ending. However, most scholars, spending life

time on the exam, even failed in winning the title of Xiucai.

Seen from the test paper No.029791 issued in the

12th year of emperor Tongzhi, with the title of Fortunate and

Destiny in Zihan?? View, it is known that Wei, T. Z., a scholar in Luoyang

county, had participated in the preliminary test for at least 10 years, finally

ranking third in the first class in the exam.

The province-level examination in Ming and Qing dynasties

was held once every three years in the provincial capitals (including Beijing).

All the scholars including Jiansheng, Yinsheng, Guansheng, Gongsheng

and so on, who passed the preliminary examination were entitled to sit for the

province-level examination. In principle, the candidate who passed the exam

would be qualified to secure the official position and take the ministry-level

exam held in the capital the following year. Wei, T. Z. would be very unlikely

to fail in the exam at the thirty-fifth place[5].

Figure 4 The

examination of Wei, T. Z. (part of 029791)

The exam papers of Wei,

C. and Wei, T. Z. filed in the museum are just the tip

of the iceberg. Only those who won the title of Juren would be qualified to

secure the official position. As for whether Wei, T. Z. himself was admitted to

an official or not, there are no supporting documents. His efforts for the

Imperial Examination for many years have finally achieved the

penetrating effect of his literary works, which tell us how difficult

to pass the civil servant exam in Qing dynasty.

Acknowledgements

The physical materials and pictures of the test papers

contained in the file are all from Luoyang Folk Museum. I would like to express

my deep gratitude to honorary director of Luoyang Folk Museum and senior

research fellow Wang Zhiyuan, who gave me guidance that finally helped to

complete the analysis of this data.

Conflicts of Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Xu, N. H. The dataset of Wei, Chun and Wei, Tingzhang??s

Imperial Examination papers archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum [J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.07.02.V1.

https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021

.07.02.V1.

[2] GCdataPR Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL]. DOI:

10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated 2017).

[3]

Li, S. Y.,

Hu, P. General History of Chinese Imperial Examination System (Qing dynasty) [M].

Shanghai: Shanghai People??s Publishing House, 2017: 236‒238.

[4]

Ji, X. F.

Chinese Academy Dictionary [M]. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Education Press, 1996: 689‒690.

[5]

Wang, Z. Y.,

Shang, Y. R., Wang, Q., et al. Old Paper

Gleanings (Volume 2) [M]. Xian: Sanqin Publishing House, 2017: 17‒18.