Dataset of Geo-economic Relations between the United States

and Northeast Asian Nations Based on Flow Data (2000?C2016)

Ma, T.1, 2 Li, Y. J.1 Ge, Y. J.3, 4*

1. School of Economics and Management, Hangzhou

Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China;

2. Institute for Global Innovation and

Development, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China;

3. Faculty of Geographical Science, Beijing

Normal University, Beijing 100875, China;

4. Academy of Plateau Science

and Sustainability, Xining 810008, China

Abstract: Geo-economic research is of great significance for understanding

the geographical pattern of the United States and Northeast Asia. Adhering to

the spatial connection strength model and the static potential energy formula

from physics, this paper constructs a geo-economic relationship tightness model

and geo-economic streaming potential model. We calculate the geo-economic

relationship tightness among Northeast Asian nations and the geo-economic

streaming potential between the United States and the respective Northeast

Asian nations. The variables of interest include data on investment, trade, air

cargo capacity, liner transportation capacity, the number of days needed to

establish enterprises, and the turnover time of importers. This paper describes

the overall geo-economic development patterns and evolution from two datasets

focused on trade and investment. The results data and process data were

included in these datasets. The results dataset includes: (1) the trade

tightness between Northeast Asian nations (2000?C2016); (2) the

investment tightness between Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016);

(3) the trade streaming potential between the United States and Northeast Asian

nations (2004?C2016); (4) the investment streaming potential between the United

States and Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016); and (5) the

geo-economic streaming potential between the United States and Northeast Asian

nations (2004?C2016). The dataset was archived in .xlsx format, with a data size

of 44.5 KB.

Keywords: geo-relations; geo-economics; flow data;

Northeast Asia

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2021.02.11

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2021.02.11

Dataset Availability Statement:

The

dataset supporting this paper was published and is accessible through the Digital Journal of Global Change Data

Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.03.02.V1 or https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.03.02.V1.

1 Introduction

Geo-economics is a product of the logic of geo-political

conflict being replaced with the logic of geo-economic competition under globalization[1], and is a new theory

explaining international relations. Since the 1970s, global trade and capital

flows have accelerated, and economic factors and relations have become

increasingly dominant across international affairs. Globalization and regional

integration are driving this process, along with the imminent emergence of the

geo-economic era. In this era, economic factors represent not only

geo-strategic goals of nations around the world but also an important means for

nations to achieve their geo-political goals[2].

Since Luttwak first proposed the concept of geo- economics in 1990[3],

domestic and foreign scholars have explored many avenues including the origin,

development process, and theoretical application and extensions of geo- economics[4?C6]. The emergence of

geo-economics has also led scholars to redefine the core concept of ??power??

within geo-politics and international relations[7,8].

One important aspect of geo-economic research is to

describe the evolution of geo-economic relations between nations across time

and space. Flow data can not only reflect the scale of the geo-economic flow

between nations but also highlight the changes in flow direction. This dataset

mainly consists of data on trade and investment across Northeast Asian nations,

and describes the geo-economic relationship between them.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The metadata of the Geo-economic

relation dataset between US and Northeast Asia nations (2000?C2016)[9] is summarized in Table 1.

It includes the dataset full name, short name, authors, year of the dataset,

data format, data size, data publisher, and data sharing policy, etc.

3 Method

3.1 Research Areas

Geo-security

relations across Northeast Asia face constant threats and challenges, while

geo-economic relations have steadily grown, and bilateral trade and investment

quotas have increased continuously. Even with a reduction in political

friction, economic and political development is not coordinated. It is also an

issue within Northeast Asia??s geo-economic relations, which makes Northeast

Asia a representative case for geo-economics. The dataset used in this study

includes the United States, Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, China, Russia and

North Korea.

3.2 Data Sources

The data

sources are as follows: trade data come from the United Nations Trade and

Development Database;

investment data are taken from China??s Foreign Investment Statistics Bulletin

(2003?C2016) on the website of the Ministry of Commerce

of the People??s Republic of China,

the US Bureau of Business Analysis,

and the official website of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development; the air

cargo capacity, liner transportation capacity index, the number of days

required to establish a business, and the turnover time of imported goods are

all soured from the World Bank database.

(Three indicators??the liner transportation capacity index, the number of days

required to establish a business, and the turnover time of imported goods??are

not included in the statistics for North Korea. To replace these, the dataset

uses the corresponding data of the ??least developed nations?? defined by the

World Bank.) In order to ensure uniformity across the dataset, only trade data

from the time period 2000?C2016 were used in this study, while investment data

were selected between 2004?C2016. The final comparison

of geo-economic relations incorporates complete data between

2004?C2016. As the size and units differ across the dataset, SPSS19.0 is

used to standardize the data before eliminating the influence of dimensions.

Table 1 Metadata summary of the Geo-economic relation dataset between US and

Northeast Asia nations (2000?C2016)

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset

full name

|

Geo-economic

relation dataset between US and Northeast Asia nations (2000?C2016)

|

|

Dataset

short name

|

Geo-economic_US_NE_Asia

|

|

Authors

|

Ma, T., School of Economics and

Management, Hangzhou Normal University; Institute for Global Innovation and

Development, East China Normal University; mateng0119@163.com.

Li, Y. J., School of Economics and

Management, Hangzhou Normal University; liyijie199712@163.com.

Ge, Y. J., Faculty of Geographical

Science, Beijing Normal University; Academy of Plateau Science and

Sustainability; geyj@bnu.edu.cn.

|

|

Geographical

region

|

United

States, Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, China, Russia, North Korea

|

|

Year

|

2000?C2016

|

|

Data

format

|

.xlsx

Data

size 44.5 KB

|

|

Data

files

|

Raw

data of investment, trade, air cargo capacity, liner transport capacity

index, the number of days needed to start a business, and the turnover time

of imported goods across Northeast Asian nations (2000?C2016); trade tightness

between Northeast Asian nations (2000?C2016); investment tightness between

Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016); trade, investment, and geo-economic

streaming potential between the United States and Northeast Asian nations

(2004?C2016)

|

|

Foundations

|

National

Natural Science Foundation of China (41871128, 41661033, 41701133); Major

Programme of the National Social Science Foundation of China (16ZDA041);

Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA20100311)

|

|

Data

publisher

|

Global

Change Research Data Publishing & Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No.

11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data

sharing policy

|

Data from

the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets

(in the Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository), and

publications (in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy

includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the

Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to

citation; (3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service

providers, are welcome to redistribute Data subject to written permission

from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution

license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new

datasets, the ??ten per cent principal?? should be followed such that Data

records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while

sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[10]

|

|

Communication

and

searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR, Crossref, DCI, CSCD, CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

3.3

Algorithms

3.3.1 The Construction of

a Geo-economic Relations Tightness Model

The spatial connection strength model has previously been

used in geography research, and it can comprehensively and objectively describe

the spatial connection strength of the research object [11]. Here,

the spatial linkage strength model is used to measure the tightness of trade

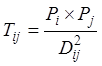

and investment linkages among Northeast Asian nations. The equation is:

(1)

(1)

where Tij

is the strength of the trade (or investment) relationship between the two

nations; Pi and Pj represent the mutual

exports (or investment) between nation i

and nation j, respectively; and Dij is the spherical distance

between the two nations.

3.3.2 Construction of the Geo-economic Streaming Potential Model

Here, we use the static potential energy formula from

physics to analyze the geo-economics streaming potential within trade and

investments.

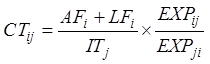

(1) At the trade level, the equation is:

(2)

(2)

where GeoTij

(Geo-trade) represents the trade flow between i and j; EXPij is the total export

volume of nation i to nation j; whereas EXPji is the total export volume of nation j to nation i; CTij is the

trade flow channel index of the nation; and

r is the spherical distance between i

and j. The size of the trade flow

channel index CTij is

mainly dependent on the transportation capacity and convenience of goods. This

article defines the trade flow channel index as being related to its

transportation volume and turnaround time. The equation is:

(3)

(3)

where AFi

is the air cargo capacity of nation i;

LFi is the liner

transportation capacity of nation i; ITj is the turnaround time of

nation j??s imports; and EXPij/EXPij is the proportion of nation i??s exports to nation j compared to nation i??s total exports that year.

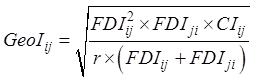

(2) At the investment level, the equation is:

(4)

(4)

where GeoIij

(Geo-investment) represents the investment flow of i and j; FDIij is the

amount of foreign direct investment from nation i to nation j; FDIji is the amount of

foreign direct investment from nation j

to nation i; CIij is the investment flow channel index from nation j to nation i; and r is the

spherical distance between i and j. The degree of market openness of a

nation has a channel restrictive effect on investment. The market openness of

target nation j is divided into five

categories on a Likert scale comprising ??very open??, ??relatively open??,

??normal??, ??relatively closed??, and ??very closed??. We take the

five points from the United States, and compare the other nations with the

United States in turn and assign them a score according to an expert scoring

method. Here, we draw on relevant research for scoring[12] and

assign Japan and South Korea four points each, Mongolia and China three points,

Russia two points, and North Korea one point, according to the moment when each

nation joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) which could have led to

changes in the value. At the same time, the factor of the time required to

establish a business in the target nation has been used by some scholars to

indicate the factors of investment thresholds and obstacles[13].

From this, the investment flow

channel index (CIij) equation is:

(5)

(5)

where Sj is

the Likert scale score of the market openness of target nation j, and BRj is the number of days required to start a business

in target nation j.

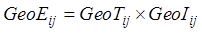

(3) The geo-economic streaming potential model is:

(6)

(6)

where GeoEij

(Geo-economic relation) is the geo-economic flow of the two nations i and j,

which is used to reflect the geo-economic relationship

between the two nations. The higher the score the stronger the geo-economic

relationship is, the lower the score, the weaker the relationship.

4 Data

Results

4.1 Data Composition

This

dataset has a national spatial resolution and covers the United States, Japan,

South Korea, Mongolia, China, Russia, and North Korea, including the results

and processing data. The results data consist of:

(1) the

trade tightness between Northeast Asian nations (2000?C2016);

(2) the

investment tightness between Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016);

(3) the trade streaming

potential between the United States and Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016);

(4) the investment

streaming potential between the United States and Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016); and

(5) the geo-economic

streaming potential between the United States and Northeast Asian nations (2004?C2016).

The processing data in the attachment contains

the raw data of investment, trade, air cargo capacity, liner transport capacity

index, the number of days needed to start a business, and the turnover time of

imported goods downloaded from the United Nations Trade and Development

Database, China??s Foreign Investment Statistics Bulletin (2003?C2016), the US Bureau of Business Analysis, the

official website of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development,

and the World Bank database.

4.2 Data Results

4.2.1 Geo-economic Tightness

In terms of trade, from 2000 to 2016 the level of trade

tightness between the United States and Russia,

compared to other nations in Northeast Asia, continuously improved. After 2010,

the degree of trade tightness between China and the United States was

significantly higher than that between the United States and other Northeast

Asian nations, while Mongolia and North Korea were in a low static state

compared to other nations.

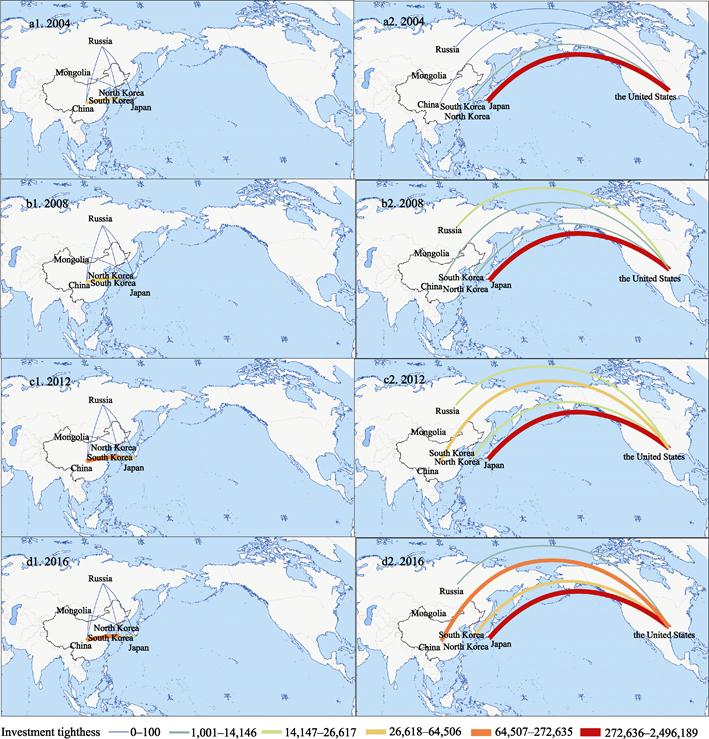

In terms of investment, in 2004 the scale of investment

flows across Northeast Asian nations was generally low, but this situation

began to change in 2008. The investment flows from the United States, Japan,

Russia, South Korea and China increased significantly. This shows that an

investment flow network with the United States as the core was gradually

forming. By 2012, this core position of the United States was further

consolidated, especially considering the improved investment tightness with

China, and the investment tightness between China, Japan and South Korea also

significantly increased. During this period, China gradually formed another

core. In 2016, the central position of the United States in the investment flow

network in Northeast Asia was even stronger, and the investment tightness

between China and other nations had greatly improved. In this way, China and

the United States formed a dual center pattern in the investment flow network.

Figure

1 Spatio-temporal evolution of the trade tightness between the United

States and Northeast Asian nations during 2000?C2016

4.2.2 Geo-economic Streaming

Potential

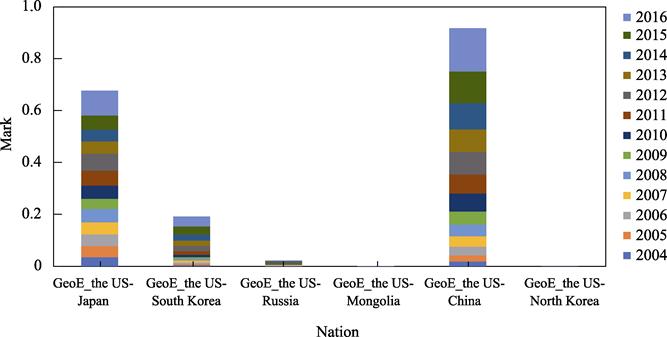

The United States and Northeast Asian

nations had low overall scores on geo-economic streaming potential, but this

continued to rise, especially after 2009. The strength of the United

States?CChina currents began to surpass that of the United States?CJapan currents

around 2008 and continued to rise, becoming the most important bilateral

current in Northeast Asia. In terms of economic relations, the United

States?CSouth Korea rising geo-economic streaming potential followed closely

behind; the remaining geo-economic trends between United States?CRussia, United

States?CMongolia and United States?CNorth Korea rose every year, but remained in

a low and static state. Compared with United States?CChina, United States?CJapan,

and United States?CSouth Korea, the strength of the geo-economic flow of United

States?CRussia, United States?CMongolia and United States?CNorth Korea remained

weak, which was consistent with the performance of trade and investment flows.

Figure 2

Spatio-temporal evolution of the investment

tightness between the US and Northeast Asian nations during 2004?C2016

Figure 3 Geo-economic streaming potential between the US

and Northeast Asian nations during 2004?C2016

5 Conclusion

This dataset uses flow data, introduces the spatial

connection strength model and static potential energy formula, and evaluates

geo-economic relations from the two perspectives of trade and investment. The

improved geo-economic flow potential model based on the static potential energy

formula can describe the strength and dynamic changes of ??flow?? within

geo-economics well, and the channel index in the model is also an important

factor to modify the spatial distance across a geo-economy. In evaluating

geo-economic flow, the product of trade and investment flow is also selected

because there is no relevant method or associated research to determine the

weight of investment and trade in geo-economic relations. Calculating the

product makes the two mutually weighted, thus achieving the effect of

comprehensive evaluation of geo-economic relations.

At present, the model used in this dataset can only analyze

the geo-economic relationship between two nations, while there are still some

deficiencies in the study of trilateral or multilateral relations. At the same

time, although the quantitative model was verified through its usage, its

potential for universal applicability needs to be further tested, and the

weight of investment and trade also needs to be further studied.

Author Contributions

Ge, Y. J. and Ma, T. designed the overall dataset development; Ma,

T. collected the statistical data; Ma,

T. designed the model; Li, Y. J.

wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no

conflicts of interest.

References

[1]

Wang, L. M., Mou, Ch. F., Lu, D. D. Changes in driving forces of

geopolitical evolution and the new trends in geopolitics studies [J]. Geographical

Research, 2016, 35(1): 3?C13

[2]

Ni, Sh. X. China??s Geopolitics and its Strategic Studies [M].

Beijing: Economic Science Press, 2015: 23?C25.

[3]

Luttwak, E. N. From geopolitics to geo-economics: logic of

conflict, grammar of commerce [J]. National Interest, 1990, 20(20): 17‒23.

[4]

Luttwak, E. N. Turbo Capitalism, Winners and Losers in the Global

Economy (Trans. by Chu, L. Y.) [M]. Beijing: Guangming Daily

Publishing House, 2000.

[5]

Li, D. R. Theoretical schools and development trend of

geo-economics [J]. Journal of Zhongnan University of Economics & Law, 2009(1): 26?C29, 111.

[6] Geoffrey, P. Geopolitics: Past, Present and Future (Trans.

by Liu, C. D.) [M]. Beijing: Xinhua Press, 2003.

[7]

Keohane, R. O., Nye, J. S. Power and Interdependence [M]. Boston:

Little, Brown, 1977.

[8]

Mead, W. R. America??s Sticky Power [Z]. Foreign Policy, 2004.

[9]

Ma, T., Li, Y. J., Ge, Y. J. Geo-economic relation dataset between

US and Northeast Asia nations (2000?C2016) [J/DB/OL]. Digital

Journal of Global Change Data Repository, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.03.02.V1. https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.03.02.V1.

[10]

GCdataPR Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL]. https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated

2017).

[11]

Xi, G. L., Zhen, F., Zhang, M., et al. Spatio-temporal evolution and regional connection of online

consumption: a case study on Jingdong Mall [J]. Scientia Geographica Sinica,

2015, 35(11): 1372?C1380.

[12]

Sun, L. J., Sun, L. X. Market openness and economic fluctuation:

the case of East Asia and China [J]. Economic Research Journal, 2005(6):

69?C81.

[13]

Zilibotti, F. Growing and slowing down like China [J]. Journal

of the European Economic Association, 2017, 15(5): 943?C988.