An Analysis of Family Property Division Dataset Archived in

Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum (1408‒1949)

Li, Z. Z.

Luoyang Folk Museum, Luoyang

471000, China

Abstract: The dataset of Family property division

contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum (1408–1949) has a collection of 98 digital

documents of the family property division contracts from 1408 to 1949, spanning

541 years from Ming and Qing dynasties to the Republic of China, in which, 3

from Ming dynasty, 61 from Qing dynasty, and 34 from the Republic of China. The

dataset is characterized by continuity in time span and completeness in

content. The dataset includes: (1) photos of 98 family property division

contracts named after the archive code; (2) statistics of each family property

division contract, including the number, name, archived code, dynasty,

material, size, complete condition and picture. The dataset, archived in .jpg

and .xls data formats, consists of 99 data files with data size of 386 MB

(compressed into one single file with 382 MB).

Keywords: family property division contract; history

and culture; Ming and Qing dynasties; the Republic of China; 1408-1949

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2021.04.12

CSTR: https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.14.2021.04.12

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset

supporting this paper was published and is accessible through the Digital Journal of Global Change Data

Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2021.07.06.V1 or https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.07.06.V1.

1

Introduction

The

traditional practice of family property division has been passed down for a

long time. Tong, Enzheng clearly pointed out in Cultural Anthropology: ??Since

the humans come to this world, the family is where the longest lasting and

common relations among people derive from, and where men and women get married,

the division of labor occurs, offspring get reproduced and relatives are

formed. The family is also where all social organizations depend on. The family

property division, vertically speaking, refers to the family property passed

from father to son; horizontally speaking, refers to the family property

distributed between brothers. The family property division is also a process of

redefinition of the rights and obligations among family members and the

redistribution of family property, and serves as the starting point of the

family reproduction which can dynamically establish ties for the shrinking

families and newborn families. Therefore, it plays an important role in connecting

the preceding with the following.??[1]. The indenture document, as

its name implies, refers to the written evidence for family property division,

including the contractual documents about the inheritance of family property

from which the legal binding force may have. According to the

interpretation in Ciyuan, an account of the history of a particular word, the

indenture document is the contract on basis of which the family property is

analyzed and distributed. The document is directly derived from the custom that

ordinary Chinese people divide their families and property after their sons

become adults. The making of indenture document is usually completed by a

number of inherent steps, and it can be enforced by the local clan, who can

ensure its execution comparable to that of official legal documents.

The Family property

division contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum

(1408‒1949), has a collection of 98 digital documents of the family property

division contracts from 1408 to 1949, spanning 541 years from Ming and Qing

dynasties to the Republic of China. From the perspective of such indenture

document which helps people to know the internal mechanism of family operation

at that time, this paper has conducted the study in a thematic and systematic

way. The family property division contracts in this dataset, have provided

historical basis for us not only to comprehend the social, cultural and

economic situation at that time, but to study the social relations from which

the self-regulating governance system is built on the basis of the moral and

ethical education within families. Therefore, it is of significance to study

the relationship between moral and legal litigation under patriarchal clan

system on resolving disputes within families at that time, and of significance

to build the social management system based on contract spirit.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The

metadata of Family property division contract dataset archived by Luoyang

Indenture Documents Museum (1408-1949)[2]

is summarized in Table 1.

3 Content of the Dataset

The

list of catalogue of Family property division contract dataset archived by

Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum (1408‒1949) can be seen in Table 2, with

each provided with the information including the number, name, dynasty, paper

type, size, collection location, preservation status and others.

4 Data Results and Discussion

4.1 Materials and Names of the Dataset

It is recorded from the

list of each document in the dataset mentioned above that the materials of these

documents are mostly velour paper, straw paper (e.g., the red straw paper used

for No. 71 during the Republic of China by Liu, Dasheng et al) and rice paper. Other materials are seldom used with

exception that the large-size red paper is applied for No. 48 and cotton cloth

for No. 56, which were rarely seen among all documents, reflecting that

property division was taken seriously and a strong sense of ceremony should be

provided.

From the perspective of the naming of these documents, there are

many appellations, such as ??Fenguan??, ??Jiushu??, ??Xidan??, ??Xiju?? , ??Geteng??,

??written pledge??, ??division document??, ??Qifengzi?? and so on[4]. Some

have profound meanings, for example, ??Guan?? closely associated with ??Guanwen??

and ??Guanyue?? (a document used in ancient times when officials at the same

level questioned each other), which can be found in The Enlightened Judgments,

Ching-ming Chi: The Sung Dynasty Collection. ??Document of Jiu?? is also an

Table 1 Metadata summary of Family

property division contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents

Museum

|

Items

|

Description

|

|

Dataset full name

|

Family property division contract dataset archived by Luoyang

Indenture Documents Museum

|

|

Dataset short name

|

FamilyPropertyDivisionContracts

|

|

Author

|

Li, Z. Z., Luoyang Folk Museum, carter_666@qq.com

|

|

Geographical

region

|

Shanxi, Henan

|

|

Year

|

Ming and Qing dynasties to the Republic of China (1408–1949)

|

|

Data format

|

.jpg, .pdf

|

|

Data files

|

(1) 98 digitized images of indenture documents, named after

filing codes

(2) Statistical table of indenture documents, including serial

number, name, filing code, age, texture, size, condition and thumbnail of

documents

|

|

Data size

|

382 MB (compressed into one single file with 6.77 MB)

|

|

Data

publisher

|

Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository,

http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No.

11A, Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data

sharing policy

|

Data from

the Global Change Research Data Publishing & Repository includes metadata, datasets

(in the Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository), and

publications (in the Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery). Data sharing policy

includes: (1) Data are openly available and can be free downloaded via the

Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to citation;

(3) Users, who are by definition also value-added service providers, are

welcome to redistribute Data subject to written permission

from the GCdataPR Editorial Office and the issuance of a Data redistribution

license; and (4) If Data are used to compile new

datasets, the ??ten per cent principal?? should be followed such that Data

records utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while

sources should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[2]

|

|

Communication

and searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR, Crossref, DCI, CSCD,

CNKI, SciEngine, WDS/ISC, GEOSS

|

Table 2 List of Family property contracts of Family property division

contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum (1408‒1949)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in

a dynasty (year)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in

a dynasty (year)

|

|

01

|

Family property division

contract of Wang, Yu and Wang, Zai

|

The 6th year during

the reign of Emperor Yongle in Ming dynasty (1408)

|

11

|

Family property division

contract of Yang, Weiren?? second son Yang, Zhi

|

The 4th year during

the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1726)

|

|

02

|

Family property division

contract of Nan, Jigang, et al.

|

The 47th year during

the reign of Emperor Wanli in Ming dynasty (1619)

|

12

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao, Yingxian and Zhao, Yingxian

|

The 9th year during

the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1731)

|

|

03

|

Family property division

contract of Wang, Quan??s three sons

|

The 12th year during

the reign of Emperor Chongzhen (1639)

|

13

|

Family property division

contract of Wang, Boyu and Wang, Boxiang

|

The 11th year during

the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1733)

|

|

04

|

Family property division

contract of Lin, Huaiyu??s son and Lin, Huaibao??s son

|

The 18th year during

the reign of Emperor Shunzhi (1661)

|

14

|

Grain and money division

document of Wang??s five brothers and their mother

|

The 12th year during

the reign of Emperor Yongzheng (1734)

|

|

05

|

Family property division

contract of Shi, Ende??s three sons

|

The 12th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1673)

|

15

|

Family property division

contract of Bai, Yongting and his two nephews

|

The 5th year during

the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1740)

|

|

06

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao, Zicheng

|

The 34th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1695)

|

16

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao??s three brothers

|

The 7th year during

the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1742)

|

|

07

|

Family property division

contract of Nan, Xinghuan??s three sons

|

The 34th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1695)

|

17

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s brothers

|

The 12th year during

the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1747)

|

|

08

|

Guo and Qing??s family property

division contract

|

The 48th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1709)

|

18

|

Family property division

contract of Wang??s four brothers

|

The 54th year during

the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1789)

|

|

09

|

Family property division

contract of Shi, Liangcai??s two sons

|

The 52th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1713)

|

19

|

Family property division

contract of Wu??s brothers

|

The 57th year during

the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1792)

|

|

10

|

Family property division

contract of Shi??s son

|

The 57th year during

the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1718)

|

20

|

Family

property division contract of Wang, Cangbao, and Wang, Cangtong

|

The 1st year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1795)

|

(To be continued on the

next page)

(Continued)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in a

dynasty (year)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in a dynasty (year)

|

|

21

|

Water use contract of Du, Ziyao

and Du, Ziquan

|

The 2nd year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1799)

|

40

|

Family property division contract

of Zhang??s two brothers

|

The 4th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1865)

|

|

22

|

Property division testament of

Li??s mother

|

The 14th year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1809)

|

41

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao, Xuesheng??s two sons

|

The 8th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1869)

|

|

23

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s two brothers

|

The 14th year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1809)

|

42

|

Family property division

contract of Wang, Boran

|

The 10th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1871)

|

|

24

|

Family property division

contract of three brothers (Defa, Mingfa, Renfa)

|

The 23th year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1818)

|

43

|

Family property contract of Yu,

Pixian and nephew Taicheng on division of workshop

|

The 11th year during

the Reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1872)

|

|

25

|

Contract of Zhang, Geng and Hao,

Wenming house delimitation

|

The 23th year during

the reign of Emperor Jiaqing (1818)

|

44

|

Family property division

contract of Dong??s two brothers

|

The 12th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1873)

|

|

26

|

Family property division

contract of Li, Yongde and his uncle Li, Xiu

|

The 4th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1824)

|

45

|

Family property division

contract on Liang, Zhi??an begging

his mother for farmland and money

|

The 13th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1874)

|

|

27

|

Family property division

contract of Wu, Yongke

|

The 6th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1826)

|

46

|

Family property division

contract on Liang, Zhixiu, wife and son begging his mother for farmland and

money

|

The 13th year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1874)

|

|

28

|

Family property division contract

of Song??s two brothers

|

The 8th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1828)

|

47

|

Family property division

contract of Li, Bingcan

|

The 5th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1879)

|

|

29

|

Family property division

contract of nephew and uncle of Cao family

|

The 24th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1844)

|

48

|

Family property division

contract of Chang??s three brothers

|

The 19th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1893)

|

|

30

|

Family property division

contract of four members of the Same Clan

|

The 25th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1845)

|

49

|

Family property division

contract of Ma??s two brothers

|

The 19th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1893)

|

|

31

|

Family property division

contract of Liang, Yunzhi??s three sons

|

The 26th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1846)

|

50

|

Family property division contract of Liang, Zhiwang??s younger

brother Zhi, Dian, Zhi, Jian and his nephew??s Dianyue, etc.

|

The 20th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1894)

|

|

32

|

Family property division contract

of Zhao??s two brothers

|

The 28th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1848)

|

51

|

Family property division

contract of Liu??s two brothers

|

The 20th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1894)

|

|

33

|

Family property division

contract of Gao??s two brothers

|

The 28th year during

the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1848)

|

52

|

Family property division

contract of Dang??s three brothers

|

The 22nd year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1896)

|

|

34

|

Family Property Division Contract

of Wang??s Two Nephews

|

The 1st year during

the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1851)

|

53

|

Family property division

contract of Ma??s two brothers

|

The 22nd year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1896)

|

|

35

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao??s nephews and sons

|

The 3rd year during

the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1853)

|

54

|

Family property division

contract of Zhao??s three brothers

|

The 25th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1899)

|

|

36

|

Family

property division con-

tract of

Liang, Yunzhi??s five sons (kept by the 3rd son)

|

The 8th year during

the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1858)

|

55

|

Family property division

contract of Heidan

|

The 26th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1900)

|

|

37

|

Family property division

contract of Liang Yunzhi??s Five Sons (kept by the 2nd and 4th

sons)

|

The 8th year during

the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1858)

|

56

|

Family property division

contract of Huang, Yongdeng

|

The 29th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1903)

|

|

38

|

Family

property division con-

tract of

Liang, Yunzhi??s five sons (kept by the 5th son)

|

The 8th year during

the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1858)

|

57

|

Family property division

contract of Chang??s four sons

|

The 30th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1904)

|

|

39

|

Family property division

contract of Yu, Pixian and nephew

Taicheng

|

The 2nd year during

the reign of Emperor Tongzhi (1863)

|

58

|

Family property division

contract of Lan??s two brothers

|

The 31st year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1905)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(To be continued on the

next page)

(Continued)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in

a dynasty (year)

|

No.

|

Name

|

Reign of emperor in

a dynasty (year)

|

|

59

|

Family property division

contract of Du?? two brothers

|

The 33rd year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1907)

|

79

|

Family property division

contract of Yutang and Taiping

|

The 13th year of Republic of China (1924)

|

|

|

60

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s two brothers

|

The 34th year during

the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1908)

|

80

|

Family property division

contract of Liang??s two brothers

|

The 14th year of Republic of China (1925)

|

|

|

61

|

Family property division

contract of uncle Zhao and his nephew

|

The 1st year during

the reign of Emperor Xuantong (1909)

|

81

|

Family property division

contract of Liang??s four brothers

|

The 15th year of Republic of China (1926)

|

|

|

62

|

Family property division

contract of Liang??s four brothers

|

The 2nd year during

the reign of Emperor Xuantong (1910)

|

82

|

Family property division

contract of Cao, Choutai

|

The 16th year of Republic of China (1927)

|

|

|

63

|

Family property division

contract of Wang??s two brothers

|

The 2nd year during

the reign of Emperor Xuantong (1910)

|

83

|

Family property division

contract of Shang??s three brothers

|

The 16th year of Republic of China (1927)

|

|

|

64

|

Family property division

contract of Wang??s two brothers

|

The 3rd year during

the reign of Emperor Xuantong (1911)

|

84

|

Family property division

contract of Lu, Jinyong??s four sons

|

The 17th year of Republic of China (1928)

|

|

|

65

|

Family property division

contract of Liang??s two brothers

|

The 2nd year of Republic of China (1913)

|

85

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s three brothers

|

The 17th year of Republic of China (1928)

|

|

|

66

|

Family property division

contract of Yang??s son

|

The 2nd year of Republic of China (1914)

|

86

|

Family property division

contract of Zhang??s four brothers

|

The 17th year of Republic of China (1928)

|

|

|

67

|

Property division contract of Wang??s family

|

The 3rd year of Republic of China (1914)

|

87

|

Family property division

contract of Ning??s three brothers

|

The 18th year of Republic of China (1929)

|

|

|

68

|

Family property division

contract of Hu??s two brothers

|

The 3rd year of Republic of China (1914)

|

88

|

Family property division

contract of Du??s two brothers

|

The 18th year of Republic of China (1929)

|

|

|

69

|

Family property division

contract of uncle Li and his nephew

|

The 6th year of Republic of China (1917)

|

89

|

Family property division

contract of Yin??s two brothers

|

The 19th year of Republic of China (1930)

|

|

|

70

|

Property division contract of

Ling??s three families

|

The 9th year of Republic of China(1920)

|

90

|

Family property division

contract of Song??s three brothers

|

The 19th year of Republic of China (1930)

|

|

|

71

|

Family property division

contract of Liu, Dasheng et al.

|

The 10th year of Republic of China (1921)

|

91

|

Family property division

contract of Chen, Yuntai and Chen, Yunzhong

|

The 19th year of Republic of China (1930)

|

|

|

72

|

Family property division

contract of Zhang??s four brothers

|

The 11th year of Republic of China (1922)

|

92

|

Family property division

contract of Hu??s two brother

|

The 24th year of Republic of China (1935)

|

|

|

73

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s three brothers

|

The 11th year of Republic of China (1922)

|

93

|

Family property division

contract of Xing?? three brothers

|

The 25th year of Republic of China (1936)

|

|

|

74

|

Family property division

contract of uncle Zhang, Jingzhao and his nephew Zhang, Yurong

|

The 11th year of Republic of China (1922)

|

94

|

Family property division

contract of Liu, Yuankai and Liu, Yuanbiao

|

The 26th year of Republic of China (1937)

|

|

|

75

|

Family property division

contract of Guo??s three brothers

|

The 12th year of Republic of China (1923)

|

95

|

Family property division

contract of Guo??s two sons

|

The 27th year of Republic of China (1938)

|

|

|

76

|

Family property division

contract of Xu, Yong-

xiang??s farmland and house

|

The 12th year of Republic of China (1923)

|

96

|

Family property division contract

of Yuan, Dagang and Yuan, Tianyou (father and son) on breaking off their

relationship

|

The 33rd year of Republic of China (1944)

|

|

|

77

|

Family property division

contract of Xu, Sixiang??s land and house

|

The 12th year of Republic of China (1923)

|

97

|

Family property division

contract of Yang??s five brothers

|

The 36th year of Republic of China (1947)

|

|

|

78

|

Family property division

contract of Li??s five brothers

|

The 13th year of Republic of China (1924)

|

98

|

Family property division

contract of Yu, Rong, Yu, Ru-hua and their nephews

|

The 38th year of Republic of China (1949)

|

|

|

Table 3 Classification of names of Family property division

contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum

|

|

Names of family

property

division contract

|

Quantity

|

|

Family property

division contract

|

63

|

|

Zhizhao, Geju,

Wenyue, Juxi, Fendan

|

11

|

|

Fenshu

|

11

|

|

Bodan, Fenboshu,

Fenboyue

|

5

|

|

Gift document

|

2

|

|

In-charge written

document, separate written document

|

2

|

|

Demarcation

contract

|

1

|

|

Geteng

|

1

|

|

Nianjiu

|

1

|

|

Fenguan

|

1

|

|

Table 4 Statistics of reign of emperor and

quantity of collected documents archived in Luoyang Museum of Indenture

Documents

(98 pieces in total)

|

|

Reign of emperor

|

Quan-tity

|

Reign of

emperor

|

Quantity

|

|

Emperor Yongle

|

1

|

Emperor Wanli

|

1

|

|

Emperor Chongzhen

|

1

|

Emperor Shunzhi

|

1

|

|

Emperor Kangxi

|

6

|

Emperor Yongzheng

|

4

|

|

Emperor Qianlong

|

5

|

Emperor Jiaqing

|

6

|

|

Emperor Daoguang

|

8

|

Emperor Xianfeng

|

5

|

|

Emperor Tongzhi

|

8

|

Emperor Guangxu

|

14

|

|

Emperor Xunatong

|

4

|

National Republic of China

|

34

|

important

one used in family property division, very similar to drawing lots; ??Xi?? from

??Xidan?? and ??Xiju?? means cutting, indicating that sharp tools such as knives

and axes are used to cut bamboo and wood, comparable to dividing the family

property. From the expression of ??Geteng?? or vine cutting, ??Teng?? or vine is

generally attached to surrounding or leaning on a big tree, therefore, ??Geteng??

means to cut these vines open and to rid the entanglements from which some are

of primary importance and some of secondary importance. Generally speaking,

family property division refers to the fact that parents passed on their

property to their sons, with parents likened as a tree and their sons as a vine

in the property division contract. As for the writing of ??Qifengzi??, it??s

synonymous with document of family property division. Due to the fact that

almost all documents are written for at least two brothers or more and the

property division contract is unnecessary for one-son family, all children need

to keep one copy for each. To prevent cheating or to ensure the authenticity of

each document, all copies of each document should be stacked together with a

unified writing on the junction of the edges of them. Contract of family

property division is an effective proof for the family separation, illustrating that the verbal statement cannot be

dependable but the written proof can do. As far as the names of these documents

are concerned, most of them are called ????????

or property division contract, accounting for 64% while others like ??Wenyue??,

??Zhizhao??, ??Geju??, ??Xiju?? and ??Fendanshu?? account for 11%, and ??Fenshu?? alone

accounts for 11% as well. Others such as ??Geteng??, contract book, written

pledge and etc only take up a small share (seen in Table 3).

According to the 98

contracts of family property division archived in Luoyang Museum of Indenture

Documents, it is found that the earliest one is written in the sixth year

during the Reign of Emperor Yongle in Ming dynasty (1408) and the latest one

in the thirty-eighth year of National Republic of China (1949), with these

documents spanning 541 years from Ming and Qing dynasties to the Republic of

China (seen in Table 4). In terms of quantity, most of them were from the Qing

dynasty to the Republic of China, relatively continuous in terms of timeline.

From the aspects of text content and form, it is difficult to detect the

influence of the writing style in different dynasties on the form and wording

except for the change of the time written at the end of each document.

4.2 Format of Family Property Division Contract

Generally,

it is considered that the property division contract is widely used by folks in

the Tang dynasty when their sons grow up and live independently. A specific

format has been taking shape during the long-term use. From the 98 pieces

archived in Luoyang Museum of Indenture Documents, the content and format of

these documents have not changed much in spite of undergoing more than 500 years.

It always has the following three parts: preface, property division and

signature, from which the preface mainly describes the hardships of the parents

in earning the property, the reasons why the property should be allotted and

how to allot the property. The second part mainly records some additional

conditions and how to distribute the specific items of family property (real

estate and movable property included). At the end of the document, the three

parties, including allotter, allottee and middleman, should sign their names

and provide it with a unified writing of ??Qifengzi?? on the junction of the

document as an anti-counterfeiting proof. In some occasions, there will be

annotations for special recorded items. These parts constitute the whole format

of property division contract (Table 5).

Table

5 Format of Family property division

contract archived in Luoyang Museum of Indenture Documents

|

Format

|

Content

|

|

Preface

|

Parties involved review the family history and explain the

reasons for property division

|

|

|

Real estate: farmland, house site , real estate, workshop,

toilet, tomb, trees, etc.

|

|

|

Movable property: farm tools, livestock, furniture, daily

necessities, etc.

|

|

|

Division of land property location: land property boundary and

quantity

|

|

Property division

|

Principle of distribution: equal distribution among all

brothers, lot-drawing, designated inheritance, etc.

|

|

|

The agreement on paying parents?? old-age pension

|

|

|

annotation (supplementary explanation), date of writing

|

|

|

Signature and pledge: parties involved, relatives, middlemen,

ghostwriters and others, and signature of ?????? Sewing

characters (half book): sub-orders, contracts, sub-orders licenses, written

documents in charge, etc.

|

|

Signature (effectiveness and

execution)

|

Qifengzi: property division contract , contracts, sub-orders

license of document, written pledge, etc.

|

Take Zhao??s three

brothers during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (No. 16) as an example to

illustrate the format of property division contract.

Zhao, Qiong, the

bookkeeper, pointed out that the three sons of Zhao Shoubi, Zhao Shouzhong and

Zhao, Shouhe, inconvenient to live together, would equally divide the family

properties by drawing lots at the presence of the clansmen, including the

houses, land, property, trees and so on. Since then, each should be in charge

of their own property. If there are bullies or deceivers, the Zhao?? brothers or

the parties involved, holding the property division contract, can file a suit

against the rule breakers, who would be punished once found guilty due to their

unfilial behavior. This division document would be as a proof and be kept as an

evidence for future use.

Zhao, Shouhe has

the ownership of the first share of family property and has signed ??????. According to what has been

written in the division document, Zhao, Shouhe should be assigned to three

rooms in the residential building where family rituals take place and the

distinguished guests are welcomed, three rooms of the west wing, one small secondary

western room in the residential building and one easily-accessed toilet to its

east. In addition, Zhao Shouhe will be promised eight taels of silver for

building a house, and the third room of the residential building which is

allowed to live in for fifteen years, 1.1 mu (15 mu= 1 ha) of paddy field

located to the south of Teng??s farmland and one section of upland field in

Xifen valley. The 1.6 mu of paddy field bestowed to Dong family and the wedding

expanses for Zhao, Shouhe are excluded in the property division program.

Zhao, Shoubi has the ownership of the second

share of family property and has signed ??????. Zhao, Shoubi is assigned to the three-room homestead to the

second door of the east building, one small room, one easily-accessed toilet to

its south of the eastern residential building. In addition, Zhao, Shoubi will

be promised four taels of silver for building a house, and one small room to

the second door of the building which is allowed to live in for fifteen years,

1.1 mu of paddy field located to the south of Teng??s farmland and the third

section of upland field in Xifen valley.

Zhao, Shouzhong has

the ownership of the third share of family property and has signed ??????. Zhao, Shoubi is assigned to the

empty courtyard behind the east building, 1.1 mu of wet field located to the

south and the 4th section of upland field in Xifen valley. Guo??s

family holds the right of use over the tile kiln. For Zhao, Qiong??s own living,

1.6 mu of wet farmland, clothes and coffins are excluded in the property

division program.

|

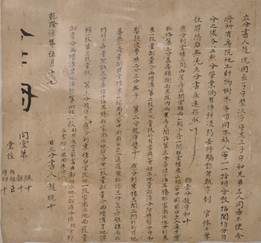

Figure 1 Family property divi-

sion contract of Zhao??s three brothers in the Qing

dynasty (No. 16, the 7th year during the reign of Emperor

Qianlong, 1742 AD)

|

May 17, the 7th

year during the reign of Emperor Qianlong

Drafter Zhao, Qiong Signature of ??????

Cousin Pei

Signature of ??????

Long

Signature of ??????

Nephew Huizu

Signature of ??????

Shouyin Signature

of ??????

Qifengzi Family Property division contract

This document,

drafted in the seventh year during the reign of Emperor Qianlong, was written

with a brush on a piece of straw paper which has a length of 31.50 cm and a

width of 29.50 cm. It tells us that the father Zhao, Qiong divided the family

property into three shares to his three sons. The last sentence ??for Zhao,

Qiong??s own living, 1.6 mu of wet farmland, clothes and coffins are excluded in

the property division program?? informs us that Zhao, Qiong spared himself some

living allowances and funeral expenses.

First of all, the

preamble of the property division contract as an indispensable part always

begins with an account of Zhao, Qiong as the drafter of the document or the

contracting party. Secondly, the reasons for the property division have been

clearly put forward, with the opening remarks of ??due to or because and etc,??

which can be seen ??the three sons of Zhao, Shoubi, Zhao, Shouzhong and Zhao,

Shouhe, inconvenient to live together??.

Then, it states out

the principle and the way of property distribution that the family properties

including the houses, land, property, trees, etc should be re-allotted equally

divide by drawing lots at the presence of the clansmen. From these 98 documents

on division of family properties, the words such as ??match evenly??, ??equally

divided??, ??equally divided into equal parts??, ??equally divided into ???? parts??, etc., can be found everywhere, which directly indicate the

principle of even division among the sons. In some documents does drawing lots

come out as well. When dividing the family, the parents must first set aside a

specific share for them to make a living, or set aside the marriage fees for

minor children by assigning farmland to the eldest grandson and the eldest son.

Finally, there are also some arrangements for public properties and punishments

as a concluding remark.

4.3 Reasons for Family Division and Its Safeguard

Policies

4.3.1 Reasons for Family Division

There are a variety of reasons for division of

family property. First and foremost, with the

increasing population and the difficulty to manage the handed-down properties,

the ancestors should pass them on to later generations who can bear the burden

of the family as soon as possible. For example, from No. 29 of Family property

division contract of nephew and uncle of Cao family in the 24th year

during the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1844), it mentions the possibilities of

the rising conflicts and tension between family members due to the increasing

population in one big family so that the division of family must be a peaceful

and preventive move. In fact, most family members pay enough attention to the

ancient teachings receive and can restrain themselves in face of some

contradictions. However, with the increase of population which may lead to the

rising domestic disharmony, they had no other choice but to divide the family

property. From No. 51 of family property division contract of Liu??s two

brothers in the 20th year during the reign of Emperor Guangxu (1898),

it also makes reference to the difficulty to deal with the family??s conflicts

and they can??t follow the example of Zhanggong?? family, in which nine

generations of family members live under one roof.

Secondly, the

family conflicts are increasing in quantity and serious in intensity in that

there are disputes between father and sons, brothers and brothers, and between

sisters-in-law who don??t agree with each other. Therefore, it contributes most

to the separation of families, which can be found more than 20 cases in the

list. From No. 31 of family property division contract of Liang, Yunzhi??s three

sons in the 26th year during the reign of Emperor Daoguang (1846) and

No. 36 of Liang, Yunzhi??s five sons (kept by the third son) in the 8th

year during the reign of Emperor Xianfeng (1858) (as shown in the figure

below), it states ??the eldest son Geng, Ji and his wife are disobedient and

uncooperative to cook and dine together; among the five sons in the not so

well-off family, Geng, Ji is so stubborn and foolish that it is difficult to

change but only to expel him out of the family instead in the 16th

year during the reign of Emperor Daoguang, the second son acts recklessly or

wildly so that he is about to be expelled for fear of future trouble.?? It tells

us that the father??s anger and disappointment with his two sons are beyond

words.

Thirdly, the family

members can??t get along well due to the disputes arising from property

ownership. Therefore, in order to avoid disputes and well manage the

properties, redistribution of family belongings becomes rather necessary.

Fourthly, to

improve the utilization of family resource and to expect their children to

become independent and get married as soon as possible, the parents, too old to

do the housework, want to divide up family property and live apart. Such

practice is a transitional, preventive and forward-looking move for the

parents, which can prevent the conflicts between children happening after they

passed away. From the documents of No. 19, No. 55 and No. 57 in Table 2, it can

be seen that to divide the family property should be in compliance with the

father??s or mother??s will when they are too old to do housework and to

revitalize the family business. What??s more, the external factor for family

property division mainly refers to the chaotic situation and famine, which take

up a relatively large proportion in all factors. Finally, the separation of

family property is also of significance to make social progress. Mr. Fei,

Xiaotong believes that the younger generation??s request for financial

independence becomes the driving force for family disintegration, which eventually

leads to the separation of family and family property passed down to the next

generation[5].

4.3.2 Principle of Property Division

The

vast majority of families not well to do can??t meet the needs of children and

grandchildren for wealth and greed is like a valley that can never be filled,

which requires the practice of fairness in redistributing the property. In some

disputes over property separation, some people don??t merely win over a large

share of wealth but for earning respect from family members. In addition, the

principle of equalitarianism is always valued most no matter who they are in a

family because the traditional Chinese people hold that inequality rather than

want is the cause of trouble. To practice the principle of equalitarianism,

first of all, not only requires an equitable and rational procedure but also

the way of implementation. In the long course of Chinese history, a variety of

equitable means were invented such as ??touching the reins for horse

redistribution and drawing lots for farmland redistribution??[6] written

in Doctrine of Shenzi in pre-Qin

period.

4.3.3 Principle of Having a Middleman

In

the past, to have a middleman or to be entrusted by relatives is usually one of

important steps for family separation. The meeting for property division

co-chaired either by the elders or by the peers is witnessed by the invited

elder of noble character and high prestige in the family clan. In the

traditional way, people always refer to the official or folk law on family property

division and the resolution would be written in the format of contract. As a

nongovernmental contact, the property division contract is legally effective in

that the agreement can be used as a valid proof for dispute mediation if both

parties violate the contract. In order to ensure the validity of the division

contract, the practice of inviting a middleman to mediate notarization is

popularly applied in contracting. Once the disputes arising from the parties

afterwards, the middleman who has attended the meeting is entitled to mediate.

It can be seen that the middleman can function as a document notary, mediator

and arbitrator. Codified Law and Magisterial Adjudication in the Qing dynasty

authored by Liang, Zhiping clarifies ??in the Qing dynasty, the role played by

the middleman in the society is extremely, whose acts have been fully

institutionalized in codified law, it is unimaginable to maintain the social

and economic order with no middleman getting involved.??[7].

5 Social and Cultural Connotation of Document of Family

Property Division

Having

a large extended family has been taken as a long-standing honor in every family

in China. However, the small-scale farming by individual owners was gradually

replaced with the capitalist economy, which called for reforming the production

order in feudal society, and the society was beset by enemies from within and

without in Ming and Qing dynasties. As a result, the patriarchal clan

system-based family relations witnessed breakdown little by little, and the

small-size family followed. As a proof for family property division, the

contract will be given full play if the property disputes arise after the

family members live apart, which surely helps people to keep faith and to run

the family in full compliance with relevant laws and regulations.

5.1 Resolution of Family Disputes

Mr.

Fei, Xiaotong has once thought that the local society of China is a society of

acquaintances and kinship because all family members were born and died in the

local area. In such society do relatives and neighbors are often very helpful,

and act as each other??s middlemen. In areas where the patriarchal clan system

is strictly implemented, the order defenders

including clan leaders can govern the locals by warning, lashing, fining,

sending to local government for punishment and deregistering the rule breakers

from family pedigree[8]. However, mediation and reconciliation

conducted by the middlemen are most commonly used for the resolving family

disputes.

As for the family division, the middleman

acts as the buffer to balance the rights and obligations of the parties

involved, by which the family disputes would be eased. Having witnessed every

steps of concluding the contract, he can be disinterested in rights and wrongs

of the matter with a whole picture of the rights and obligations of each party.

What??s more, the middleman, having the high prestige among locals and always

respected for his integrity and kindliness, has more right to say in the

neighborhood. The middleman must take responsibility for every mistake in the

conclusion of the contract from beginning to end while other people like

witnesses and notaries do not. Therefore, it can be seen that as a buffer for

resolving the disputes, the role of ??middleman?? is quite important especially

whenever the disputes between the parties arise.

5.2 Equilibration of Moral Restraint and Rule

of Law

In

the old days, the rites and statute combined are the way to maintain kinship

and human relations. Different from the modern statute, the statute of the past

is only advocated but less enforced while the role of morality and ethics can

never be underestimated in educating the folks and shaping public opinions. The

role of middleman should be more important than that of statute once the power

of public opinion and kinship are integrated. In a large extended family is

full of intricate property connections, ethical affection and even conflict. At

the same time, it also reflects the state??s recognition of the family as an

entity and recognition of the property owned by the public or the private. The

connection between extended family and the nuclear family is actually a type

within a setting of all family members. On the surface, it is an issue of

family structure and form, but an issue of power distribution among the state,

extended family and the nuclear family[9].

5.3 Contract Spirit and Patriarchal Clan

System

As

a legal act, the division of family property is not only done in the spirit of

contract, but in keeping with the provisions of local folk contract and clan

society. Seen from these 98 documents, the nuclear family, extended family and

patriarchal clan are always in the dynamic of opposition and unity in that the

private affairs of one family may be of the public affairs in the clan, a large

variety of family affairs must be taken under the management of one

institutional norm, people-to people relationship may vary in terms of the

closeness to each other while the moral principles should be impartial to

everyone[10]. The division of family property approved by

the clan society widely exists among the people, which can help to maintain the

order in rural area and can improve the self-governance of clan society.

6 Conclusion

The

document of family property division is a materialized representation of

interest relations of social structure and feudal economy. Different from

provisions of the current inheritance law in many aspects, the contract of

family property division played an important role in promoting the

self-regulating governance centered on moral and ethical education within

families, which can help to resolve disputes within families, to balance moral

restraint and rule of law, and to shape the long-term stability in the spirit

of contract. Today, it is necessary for us to study the separatio bonorum under

the specific historical environment. Only in this way can we have a deep

understanding of the profound Chinese culture with these documents scattered in

different historical stages.

Acknowledgements

The documents in this paper come either from Luoyang Folk Museum or from

the collections of Wang, Zhiyuan, a senior museologist (honorary curator of

Luoyang Folk Museum), who deserve my sincere gratitude.

Conflicts of

Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1] Tong, E. Z. Cultural Anthropology [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai People??s

Publishing House, 1989: 134.

[2]

Li, Z. Z. Family property

division contract dataset archived by Luoyang Indenture Documents Museum (1408–1949)

[J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global

Change Data Repository, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3974/

geodb.2021.07.06.V1.

https://cstr.escience.org.cn/CSTR:20146.11.2021.07.06.V1.

[3] GCdataPR Editorial Office. GCdataPR data sharing policy [OL].

https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated 2017).

[4] Tian, T. Local Materials of Civil Law [M]//The Second Statute. Beijing:

Law Press, 2002: 79.

[5] Fei, X. T. Peasant Life in China [M]. Nanjing: Jiangsu People??s

Publishing House, 1986: 46‒47.

[6] Shen, D. Z. A collection of Doctrine of Some Philosophers (Volume 1)

[M]. Beijing: Tuanjie Publishing House, 1996: 577‒578.

[7] Liang, Z. P. Customary Law of Qing dynasty: Society and State [M].

Beijing. China University of Political Science and Law Press, 1996: 121.

[8] Fei, X. T. Peasant Life in China: the Life of Chinese Peasant [M].

Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2010: 97.

[9] Zhang, G. G. Family and Society in the Tang dynasty [M]//An

Investigation of Family and Family Relations in the Tang dynasty??Learning Notes

of Dunhuang Museum on Property Division. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company Press,

2014: 84.

[10] Liu, D. S., Ling, G. P. Contract of inheritance division and local

inheritance relationship in Ming and Qing dynasties [J]. Journal of Anhui Normal University (Humanities and Social Sciences), 2010, 38(2): 193.