Dataset Development of Poyang Lake Herbivorous Wintering

Waterbird Droppings and Carex cinerascens K??kenth. Decomposition (2017)

Zhang, Q. J.1 Xia, S. X.2,3 Wu, D. L.1 Duan,

H. L.2,3* Yu, X. B.2,3*

1. Meteorological Observation

Centre, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081, China;

2. Key Laboratory of Ecosystem Network Observation and

Modeling, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China;

3. University of Chinese

Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Abstract: Based on a litterbag

decomposition experiment on Carex litter and an additive experiment with

droppings from herbivorous wintering waterbirds conducted in 2017 on the

beaches of Poyang Lake, this study systematically collected data on wetland

organic matter decomposition and carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling. This

work led to the construction of the Dataset of Poyang Lake herbivorous

wintering waterbird droppings and Carex cinerascens K??kenth.

decomposition. The results indicated that the addition of bird droppings

significantly accelerated the decomposition of Carex litter. In the

mixed treatment, the residual rates of dry matter, lignin, and cellulose of Carex

(66.80%, 61.03%, and 44.54% respectively after 150 days) were significantly

lower than those in the single Carex treatment (71.96%, 69.97%, and

62.53%). Furthermore, the nutrient release rates (Relative Return Index) of

carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus (42.73%, 53.95%, and 14.65% respectively) were

significantly higher than those in the single Carex treatment (34.91%,

17.96%, and 5.7%). The bird droppings themselves decomposed slowly but

exhibited high nitrogen and phosphorus release characteristics. This suggests

that wintering waterbirds, through excretory activities that input

allochthonous nutrients and microbial communities, likely promote the

decomposition of structural components (cellulose, lignin) of Carex and

the net release of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. This is achieved by

altering substrate composition, enhancing nutrient availability, and

stimulating microbial activity, thereby profoundly influencing wetland material cycling

processes and carbon pool dynamics. The dataset includes: (1) geo-location

information of the sample plots; (2) dry matter decomposition rate of samples;

(3) lignin decomposition data; (4) cellulose decomposition data; (5) total

carbon return; (6) total nitrogen return; and (7) total phosphorus return. It

provides a key scientific basis for revising global carbon models and the

managing of wetland ecosystems.

Keywords: dry matter; lignin; cellulose;

carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus; Poyang Lake; waterbirds

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodp.2025.04.07

Dataset Availability Statement:

The dataset supporting this

paper was published and is accessible through the Digital Journal of Global

Change Data Repository at: https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2025.09.02.V1.

1 Introduction

Litter

decomposition is a core process driving organic matter mineralization, which

plays a key regulatory role in global carbon fluxes and ecosystem material cycling[1,2]. Wetlands, as highly

productive ecosystems, lead to the continuous accumulation of wet plant (e.g., Carex)

litter due to their flooded anaerobic environment, forming important carbon and

nitrogen storage pools[3?C5].

Decomposition directly regulates nutrient turnover efficiency, soil fertility

maintenance, and biological community construction[6].

Even minor changes in its rate can significantly disrupt the

release-accumulation balance of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus elements,

triggering regional to global-scale responses in carbon and nitrogen pool dynamics[7,8].

More than 30% of

plant photosynthetic carbon fixation is stored in cellulose and lignin, whose

decomposition rates profoundly regulate the carbon cycle process[7].

As recalcitrant structural components, their content (especially lignin) is

often negatively correlated with the overall litter decomposition rate[8]. Lignin inhibits

biodegradation by enhancing cell wall resistance and is primarily decomposed by

extracellular enzymes secreted by fungi[9].

Although cellulose dominates the degradation process in the early stages of

decomposition, its main body is physically protected by lignin and can only be

effectively utilized by microorganisms after lignin decomposition[10?C12].

The dominant Carex

species on the Poyang Lake (China??s largest freshwater lake) beach exhibit

unique phenological rhythms: they sprout after water recedes in autumn, and the

aboveground parts gradually wither in winter; they undergo secondary sprouting

the following spring, until the aboveground parts die and begin decomposition

during the flooding period in April[13].

This phenological process is highly synchronized with the habitat period of

wintering waterbirds (especially herbivorous Anseriformes), providing them with

key food resources[14], making

this wetland a core hub of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway[15].

Annually, over 400,000 wintering waterbirds visit the area, with Anseriformes

accounting for more than 50% of the population[16,17].

This large bird population inputs allochthonous nutrients and microbial

communities into the wetland through excretory activities[18],

potentially accelerating the biogeochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus[19?C21].

Based on a

controlled decomposition bag experiment (with 3 treatments: Carex

litter, bird droppings, and a Carex-droppings mixture) conducted from

January to June 2017, the authors systematically quantified the residual

amounts, residual rates, and instantaneous decay coefficients of dry matter,

lignin, and cellulose, as well as the percentages of total carbon, total

nitrogen, and total phosphorus in dry matter, residual amounts, and Relative

Return Indices. By analyzing these indicators, the study aims to reveal: the

differences in the dynamics of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus release during

the decomposition of droppings from herbivorous wintering waterbirds and beach Carex

litter; and the regulatory effect of the addition of bird droppings on the

decomposition process of Carex litter. The research results will deepen

the understanding of wetland material cycling mechanisms, provide empirical

data support for the revision of global carbon models, and offer a scientific

basis for formulating adaptive wetland management strategies.

2 Metadata of the Dataset

The metadata for the Dataset of Poyang Lake

herbivorous wintering waterbird droppings and Carex cinerascens K??kenth.

decomposition[22], including the title, authors, geographical region, data format, data

size, data files, etc., is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Metadata summary of the Dataset of Poyang Lake herbivorous wintering waterbird

droppings and Carex cinerascens K??kenth. decomposition

|

Item

|

Description

|

|

Dataset full name

|

Dataset of

Poyang Lake herbivorous wintering waterbird droppings and Carex

cinerascens K??kenth. decomposition

|

|

Dataset short

name

|

DecompositionPoyangLake

|

|

Authors

|

Zhang, Q. J., Meteorological Observation Centre, China Meteorological

Administration, zhangqj@cma.gov.cn

Xia, S. X., Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, xiasx@igsnrr.ac.cn

Wu, D. L., Meteorological Observation Centre, China Meteorological

Administration, wudongli666@126.com

Duan, H. L., Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, duanhl@igsnrr.ac.cn

Yu, X. B., Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research,

Chinese Academy of Sciences, yuxb@igsnrr.ac.cn

|

|

Geographical

region

|

Poyang Lake

|

|

Year

|

2017?C2018

|

|

Data format

|

.shp,

.xlsx

|

|

Data size

|

96.4

KB

|

|

Data files

|

(1) Sample site

location information; (2) Dry matter decomposition data; (3) Lignin

decomposition data; (4) Cellulose decomposition data; (5) Total carbon

return; (6) Total nitrogen return; (7) Total phosphorus return

|

|

Data publisher

|

Global Change

Research Data Publishing & Repository, http://www.geodoi.ac.cn

|

|

Address

|

No. 11A, Datun

Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China

|

|

Data sharing

policy

|

(1) Data are openly available and can be

free downloaded via the Internet; (2) End users are encouraged to use Data subject to citation; (3) Users,

who are by definition also value-added service providers, are welcome to

redistribute Data subject to written permission from the GCdataPR Editorial

Office and the issuance of a Data

redistribution license; and (4) If Data

are used to compile new datasets, the ??ten percent principal?? should be

followed such that Data records

utilized should not surpass 10% of the new dataset contents, while sources

should be clearly noted in suitable places in the new dataset[23]

|

|

Communication and

searchable system

|

DOI, CSTR,

Crossref, DCI, CSCD, CNKI, SciEngine, WDS, GEOSS, PubScholar, CKRSC

|

3 Methods

3.1 Area of Data Collection

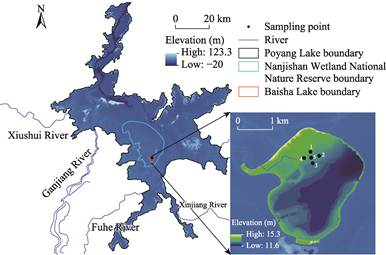

This dataset was sourced from

field collection in Baisha Lake, a typical dish-shaped lake within the Poyang

Lake Nanjishan Wetland National Nature Reserve (Figure 1). The reserve is

located in the frontal delta area of southern Poyang Lake, where 3 tributaries

of the Ganjiang River flow into the lake. The ground elevation ranges between

12 and 16 m (Wusong Elevation System). It belongs to a typical subtropical

monsoon climate zone, characterized by hot, rainy summers and cold, dry

winters. Influenced by the seasonal water level fluctuations of Poyang Lake,

the reserve exhibits distinct alternating hydrological patterns of high-water

season (generally April to September) and low-water season (generally October

to March the following year): during the high-water season, most of the grassy

meadows are submerged; as the low-water season arrives, water levels drop,

revealing a river-lake intertwined beach landscape[24,25].

This periodic hydrological variation shapes the fertile soil and favorable

hydrothermal conditions of the beach shallows, fostering diverse hygrophytic

and aquatic vegetation, with Carex, Triarrhena lutarioriparia,

and Phragmites australis dominating the community[26,27].

Among them, Carex is the most widely distributed dominant plant in

Poyang Lake, covering the beaches from the lakeshore to the waterline, hence it

was selected as the representative beach plant for this study. Carex has

a unique growth cycle: ??Autumn grass?? sprouts after water recedes in September,

growing until December?CMarch the following year when the aboveground parts

wither; ??Spring grass?? sprouts beside the incompletely dead autumn grass after

January, growing until April when submerged by lake water, ultimately dying,

becoming dormant, and decomposing underwater[28].

The aforementioned ecological mechanisms provide essential habitat and food for

many rare wintering waterbirds, thereby maintaining the region??s rich avian

diversity. Consequently, the Poyang Lake wetland is known as the ??Kingdom of

the Siberian Crane?? and the ??Paradise for Migratory Birds??, establishing its

ecological status as one of Asia??s most important wintering grounds for

migratory birds.

Figure

1 Location map

of sampling points in the Poyang Lake wetland

3.2 Field Experiment

3.2.1 Plot Setup and Sample Preparation

In late January 2017, based on

preliminary surveys of wetland vegetation and waterbird habitats, this study

established 5 fixed plots (approximately 50 m apart) within Baisha Lake in the

Nanjishan Wetland Reserve. Plot selection was primarily based on the following

principles: minimal human disturbance, frequent activity of herbivorous

waterbirds, dense bird droppings traces, and well-developed vegetation. The

selected beach was about 200 m from the waterline,

dominated by Carex cinerascens K??kenth., with vegetation coverage of

80%?C90%, plant height of 40?C60 cm, and abundant bird droppings visible on the

ground and plants. 1 decomposition experiment point was set up within each

plot, totaling 5 replicates.

3.2.2 Decomposition Experiment

The litterbag method was used. Decomposition

bags were made of 100-mesh (aperture 0.15 mm), 15 cm??20 cm white nylon

mesh, preventing sample loss while allowing microbial activity.

(1) Carex litter preparation:

Senescent Carex leaves were collected near the plots, rinsed with

deionized water, cut into 10 cm segments and mixed (to eliminate size effects).

They were then oven-killed at 120 ?? for 1 hour and oven-dried at 60 ??

to constant weight.

(2) Bird droppings sample preparation: Fresh

goose droppings (<24 h) were collected from the plots. They were oven-dried

at 60 ?? to constant weight.

(3) Initial nutrient measurement: 10.00 g of

dried samples (6 replicates each for Carex and droppings) were taken to

determine initial nutrients.

(4) Bag loading treatment: The remaining

samples were loaded into bags according to the following 3 treatments: pure

bird droppings (10 g), pure Carex litter (10 g), mixed treatment (Carex

5 g+bird droppings 5 g). A total of 105 decomposition bags were prepared.

3.2.3 Field Deployment and Sampling

Decomposition bags were deployed strictly

according to the experimental design, placing 7 bags at each of the 5 points,

covering all 3 treatments. During fixation, PVC pipes were used to secure the

bags close to the ground, ensuring they did not shift or interfere with each

other, while protecting the integrity of the native litter layer. Samples were

scheduled for retrieval on the 5th, 15th, 30th, 60th, 90th, 120th, and 150th

days after deployment. However, the experiment was terminated early due to flooding

of the plots in June that year, leading to a drastic change in the

hydrological background.

3.3 Laboratory

Experiments

Retrieved decomposition bags were cleaned in

the laboratory (removing soil, algae, etc.). Carex residues in the mixed

treatment samples were separated. All samples were oven-dried at 60 ?? to

constant weight, and the residual dry weight was measured. Samples were ball- milled

(particle size 0.06 ??m) and sealed in numbered polyethylene bags for testing.

The content of lignin and cellulose was

determined referring to the method by Zhang, et al.[29].

The total carbon and total nitrogen content in the samples were measured using

an elemental analyzer (Vario Max CN, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Germany).

Total phosphorus content was determined by inductively coupled plasma optical

emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Optima 5300 DV, Perkin-Elmer, America).

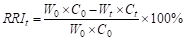

3.4 Data Processing and Analysis

The sample residual rate was calculated using

the following Equation[13]:

(1)

(1)

where, Rt represents the residual rate at

time t, Wt and W0 are the sample mass at time t and the

initial mass, respectively, in grams (g), and t is the decomposition

time in days (d).

The instantaneous decay rate (k) was calculated using the

Olson negative exponential decay model:

(2)

(2)

Transformed to:  (3)

(3)

where, k represents the instantaneous decomposition

rate at time t, A larger k value

indicates a faster decomposition rate.

Furthermore, the Relative Return Index

(RRI) was introduced to assess the release or accumulation state of elements,

calculated as:

(4)

(4)

where, Ct and C0

represent the concentration of an element at time t and the

initial time, respectively. For ease of expression, the RRI for total carbon,

total nitrogen, and total phosphorus are denoted as CRRI, NRRI, and PRRI,

respectively. A positive RRI value indicates net release of the element during

decomposition, while a negative value indicates net accumulation.

4 Data Results

4.1 Dataset Composition

The dataset consists of sample site location

information (.shp) and 1 Excel file. The Excel file includes 6 sheets, named

Dry Matter, Lignin, Cellulose, Total Carbon, Total Nitrogen, and Total

Phosphorus, respectively. These sheets contain monitoring data for these 6

indicators from 5 replicate samples on the 5th, 15th, 30th, 60th, 90th, 120th,

and 150th days of the decomposition experiment, including measured values, mean

values, and standard deviations. Detailed data descriptions for each indicator

are shown in Table 2.

Table

2 Measured indicators and their statistics

|

Indicator

|

Calculated statistics

|

|

Dry

Matter

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Residual

Rate (%)

|

Instantaneous

Decay Coefficient

|

Dry

Matter

|

|

Lignin

|

Percentage

of Dry Matter Residual Amount (%)

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Instantaneous

Decay Coefficient

|

Residual

Rate (%)

|

|

Cellulose

|

Percentage

of Dry Matter Residual Amount (%)

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Instantaneous

Decay Coefficient

|

Residual

Rate (%)

|

|

Total

Carbon

|

Percentage

of Dry Matter Residual Amount (%)

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Relative

Return Index (%)

|

Total

Carbon

|

|

Total

Nitrogen

|

Percentage

of Dry Matter Residual Amount (%)

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Relative

Return Index (%)

|

Total

Nitrogen

|

|

Total

Phosphorus

|

Percentage

of Dry Matter Residual Amount (%)

|

Residual

Amount (g)

|

Relative

Return Index (%)

|

Total

Phosphorus

|

4.2 Data Results

The

initial contents of lignin, cellulose, total carbon, total nitrogen, and total

phosphorus in the Carex and bird droppings samples are shown in Table 3.

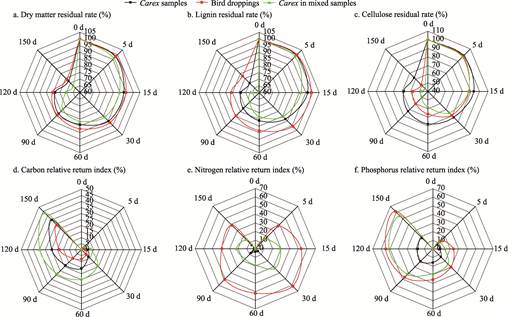

The dynamic changes in dry matter, lignin, cellulose, total carbon, total

nitrogen, and total phosphorus during the decomposition process are shown in

Figure 2.

Table

3 Initial

content of lignin, cellulose, total carbon, total nitrogen, and total

phosphorus in Carex and bird droppings samples

|

Indicator

|

Carex sample??n=6??

|

Bird droppings sample??n=6??

|

|

Mean

|

Standard deviation

|

Mean

|

Standard deviation

|

|

Total

Carbon (%)

|

43.080a

|

0.277

|

36.820b

|

1.308

|

|

Total

Nitrogen (%)

|

1.150a

|

0.060

|

1.330b

|

0.072

|

|

Total

Phosphorus (??)

|

0.970a

|

0.019

|

2.440b

|

0.093

|

|

Carbon/Nitrogen

|

37.460a

|

0.001

|

27.680b

|

0.001

|

|

Lignin

(%)

|

8.040a

|

0.328

|

4.890b

|

0.425

|

|

Cellulose

(%)

|

8.760a

|

0.581

|

7.860b

|

0.682

|

Note: Significant differences between means were tested using Tukey??s

Honest Significant Difference test. Different letters following the data

indicate significant differences between the two sample types.

As shown in Figure 2a?C2c, during the 5?C150-d

decomposition period, the residual rates of dry matter, lignin, and cellulose

differed significantly among the 3 sample types (Carex, bird droppings, Carex

in mixture). Throughout the decomposition process, the dry matter and lignin

residual rates were always lowest for the Carex in the mixture, followed

by pure Carex, and highest for bird droppings.

Figure 2 Dynamic

changes in dry matter, lignin, cellulose, total carbon, total nitrogen, and

total phosphorus during the decomposition of the three sample types

After 150 days of decomposition, the dry matter

residual rate was: Carex in mixture (66.80%) < pure Carex

(71.96%) < bird droppings (73.80%); the lignin residual rate was: Carex

in mixture (61.03%) < pure Carex (69.97%) < bird droppings

(77.40%). Throughout the decomposition process, the cellulose residual rate was

always lowest for the Carex in the mixture, followed by bird droppings,

and highest for pure Carex. After 150 days of decomposition, the

cellulose residual rate was: Carex in mixture (44.54%) < bird

droppings (50.83%) < pure Carex (62.53%).

The results of the decomposition experiment (5?C150

days) showed (Figure 2d?C2f) that the RRI for total carbon, total nitrogen, and

total phosphorus differed dynamically among the 3 sample types. The release

intensity of total carbon showed a clear hierarchical order: the lowest return

index was for bird droppings, followed by pure Carex, and highest for

the Carex in the mixture, a pattern that persisted throughout the

decomposition stage. After 150 days of decomposition, the total carbon return

index was: bird droppings (28.9%) < pure Carex (34.91%) < Carex

in mixture (42.73%). Throughout the decomposition stage, the total nitrogen and

total phosphorus return indices were always lowest for pure Carex,

followed by the Carex in the mixture, and highest for bird droppings.

After 150 days of decomposition, the total nitrogen return index was: pure Carex

(17.96%) < Carex in mixture (53.95%) < bird droppings (61.63%);

the total phosphorus return index was: pure Carex (5.7%) < Carex

in mixture (14.65%) < bird droppings (38.48%).

5 Discussion and Conclusion

Based on the decomposition bag experiment and

bird droppings addition test conducted from January to June 2017, authors

systematically analyzed the decomposition characteristics of 3 sample types: Carex

litter, bird droppings, and the Carex-droppings mixture. The study

measured the residual amount, residual rate, and instantaneous decay

coefficient of dry matter, lignin, and cellulose; simultaneously, it analyzed

the percentage in dry matter, residual amount, and RRI of total carbon, total nitrogen, and total phosphorus. This dataset

can be used to study the dynamics of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus release

during the decomposition of droppings from herbivorous wintering waterbirds and

typical beach wetland plant litter in Poyang Lake, as well as the impact of

bird droppings addition on the decomposition process of Carex litter.

The research results indicate: (1) Bird

droppings addition significantly promoted Carex decomposition. The

residual rates and decomposition rates of dry matter, cellulose, and lignin of Carex

litter and that in the mixture showed extremely significant differences.

Throughout the decomposition process, the residual rate of Carex in the

mixture was always lower than that of the single Carex sample, while the

decomposition rate was always higher, indicating that bird droppings addition

had a continuous and significant promoting effect on Carex

decomposition. (2) Element release patterns and return. Carbon, nitrogen, and

phosphorus elements overall exhibited a net release pattern. The carbon,

nitrogen, and phosphorus return indices for the Carex in the mixture

were significantly higher than those for the single Carex sample,

indicating that bird droppings addition also significantly promoted the release

and return of nutrient elements from Carex. (3) Analysis of promotion

mechanisms. The addition of bird droppings likely promotes the decomposition of

cellulose and lignin in Carex litter by altering the original component

ratio of the litter, increasing nutrient availability in the environment,

enhancing microbial colonization capacity, and stimulating the production of

extracellular degrading enzymes[20,21].

This dataset deepens the understanding of the

wetland plant litter decomposition process, and helps elucidate the ecological

role of wintering waterbirds in wetland litter decomposition and carbon,

nitrogen, and phosphorus cycling, and provides a scientific basis and data

support for optimizing habitat restoration and wetland management strategies

for waterbirds in Poyang Lake.

Author Contributions

Zhang. Q. J. designed

and implemented the field experiment, was responsible for sample collection,

laboratory analysis, data processing, and data paper writing; Xia, S. X. and

Duan, H. L. guided and assisted in the field experiment design and sample collection;

Wu, D. L. guided data quality control and data paper writing; Yu, X. B.

provided overall design for the dataset development, and guided and supervised

the experiment implementation.

Conflicts

of Interest

The

authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

[1]

Berg,

B., Mcclaugherty, C. Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon

Sequestration [M]. New York: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014.

[2]

G??rski,

A., Bło??ska, E., Lasota, J. Decomposition rate and property changes of deadwood

across an altitudinal gradient: a case study in the Babia G??ra Massif, Poland

[J]. Scientific Reports, 2025, 15(1): 28160.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14019-7.

[3]

Matthews,

E., Fung, I. Methane emission from natural wetlands: global distribution, area,

and environmental characteristics of sources [J]. Global Biogeochemical

Cycles, 1987, 1(1): 61‒86.

[4]

Roehm,

C. Respiration in Wetland Ecosystems [M]. New York: Oxford University Press,

2005.

[5]

Yang,

T. W., Sun, J. J., Li, Y. F., et al. Impact of climate-induced

water-table drawdown on carbon and nitrogen sequestration in a Kobresia-dominated

peatland on the central Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau [J]. Communications Earth &

Environment, 2025, 6: 188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02168-6.

[6]

Xiong,

S. J., Christer, N. The effects of plant litter on vegetation: a meta-analysis

[J]. Journal of Ecology, 1999, 87(6): 984‒994.

[7]

William,

D., Reddy, K. Litter decomposition and nutrient dynamics in a phosphorus

enriched Everglades Marsh [J]. Biogeochemistry, 2005, 75(2): 217.

[8]

Davis,

S., Corronado-molina, C., Childers, D., et al. Temporally dependent C,

N, and P dynamics associated with the decay of rhizophora mangle L. leaf litter

in oligotrophic mangrove wetlands of the Southern Everglades [J]. Aquatic

Botany, 2003, 75(3): 199‒215.

[9]

Schwarz,

W. H. The cellulosome and cellulose degradation by anaerobic bacteria [J]. Applied

Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2001, 56(5): 634.

[10]

Berg,

B., Laskowski, R. Litter fall [J]. Advances in Ecological Research,

2005, 38(38):19‒71.

[11]

Swift,

M., Heal, O., Anderson, J. Decomposition in Terrestrial Ecosystems [M]. Oxford:

Blackwell Scientific, 1979.

[12]

Pauly,

M., Keegstra, K. Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource

for biofuels [J]. The Plant Journal, 2008, 54(4): 559‒568.

[13]

Zhang,

Q. J., Yu, X. B., Hu, B. H. Study on the distribution characteristics of plant

communities in the Nanji Wetland of Poyang Lake [J]. Resources Science,

2013, 35(1): 42‒49.

[14]

Guan,

L., Wen, L., Feng, D. D., et al. Delayed flood recession in central

Yangtze floodplains can cause significant food shortages for wintering geese:

results of Inundation experiment [J]. Environmental Management, 2014,

54(6): 1331‒1341.

[15]

Xia,

S. X., Liu, G. H., Yu, X. B., et al. Habitat evaluation for wintering

waterbirds in Poyang Lake [J]. Journal of Lake Sciences, 2015, 27(4):

719‒726.

[16]

Tu,

Y. G., Yu, C. H., Huang, X. F., et al. Distribution and quantity of

wintering geese and ducks in Poyang Lake region [J]. Acta Agriculturae

Universitatis Jiangxiensis, 2009, 31(4): 760‒764+771.

[17]

Manny,

B., Johnson, W., Wetzel, R. Nutrient additions by waterfowl to lakes and reservoirs:

predicting their effects on productivity and water quality [J]. Hydrobiologia,

1994, 279‒280(1): 121‒132.

[18]

Chaichana,

R., Leah, R., Moss, B. Birds as eutrophicating agents: a nutrient budget for a

small lake in a protected area [J]. Hydrobiologia, 2010, 646(1):

111‒121.

[19]

Hahn,

S., Bauer, S., Klaassen, M. Quantification of allochthonous nutrient input into

freshwater bodies by herbivorous waterbirds [J]. Freshwater Biology, 2010, 53(1):

181‒193.

[20]

Zhang, Q. J., Zhang, G. S., Wan, S. X., et al. Effects of droppings from herbivorous

wintering waterbirds on decomposition process and carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus

release of Carex litter in beach wetland of Poyang Lake [J]. Journal

of Lake Sciences, 2019, 31(3): 814‒824.

[21]

Zhang,

Q. J., Zhang, G. S., Yu, X. B., et al. How do droppings of wintering

waterbird accelerate decomposition of Carex cinerascens K??kenth. litter

in seasonal floodplain Ramsar Site? [J]. Wetlands Ecology and Management,

2021, 29(4): 581‒597. DOI: 10.1007/s11273-021-09804-w.

[22]

Zhang,

Q. J., Xia, S. X., Wu, D. L., et al. Dataset of Poyang Lake herbivorous wintering waterbird

droppings and Carex cinerascens K??kenth. decomposition [J/DB/OL]. Digital Journal of Global Change Data Repository, 2025.

https://doi.org/10.3974/geodb.2025.09.02.V1.

[23]

GCdataPR Editorial Office. GCdataPR

data sharing policy [OL]. https://doi.org/10.3974/dp.policy.2014.05 (Updated

2017).

[24]

Liu,

X. Z., Hu, B. H. Comprehensive Scientific Survey of Jiangxi Nanjishan Wetland

Nature Reserve [M]. Beijing: China Forestry Publishing House, 2005.

[25]

Editorial

Committee of ??Poyang Lake Research??. Poyang Lake Research [M]. Shanghai:

Shanghai Science and Technology Press, 1988.

[26]

Wang, Y. Y., Yu, X. B., Zhang, L., et al. Seasonal variability in baseline ??15n

and usage as a nutrient indicator in Lake Poyang, China [J]. Journal of

Freshwater Ecology, 2013, 28(3): 365‒373.

[27]

Zhang,

Q. J., Yu, X. B., Qian, J. X., et al. Distribution characteristics of

dominant plant communities and soil organic matter and nutrients in the Nanji

Wetland of Poyang Lake [J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2012, 32(12):

3656‒3669.

[28]

Zhang, Q. J., Yu, X. B., Zhang,

G. S. Decomposition process and carbon and nitrogen isotope fractionation

characteristics of litter from three dominant plants in Poyang Lake wetland

[J]. Journal of Lake Sciences, 2023, 35(5): 1694‒1704.

[29] Zhang, G. S., Yu, X. B., Xu, J. Effects

of environmental variation on stable isotope abundances during typical seasonal

floodplain dry season litter decomposition [J]. Science of the Total

Environment, 2018, 630(1): 1205‒1215.